As competition in the dating market heats up, many men are opting out

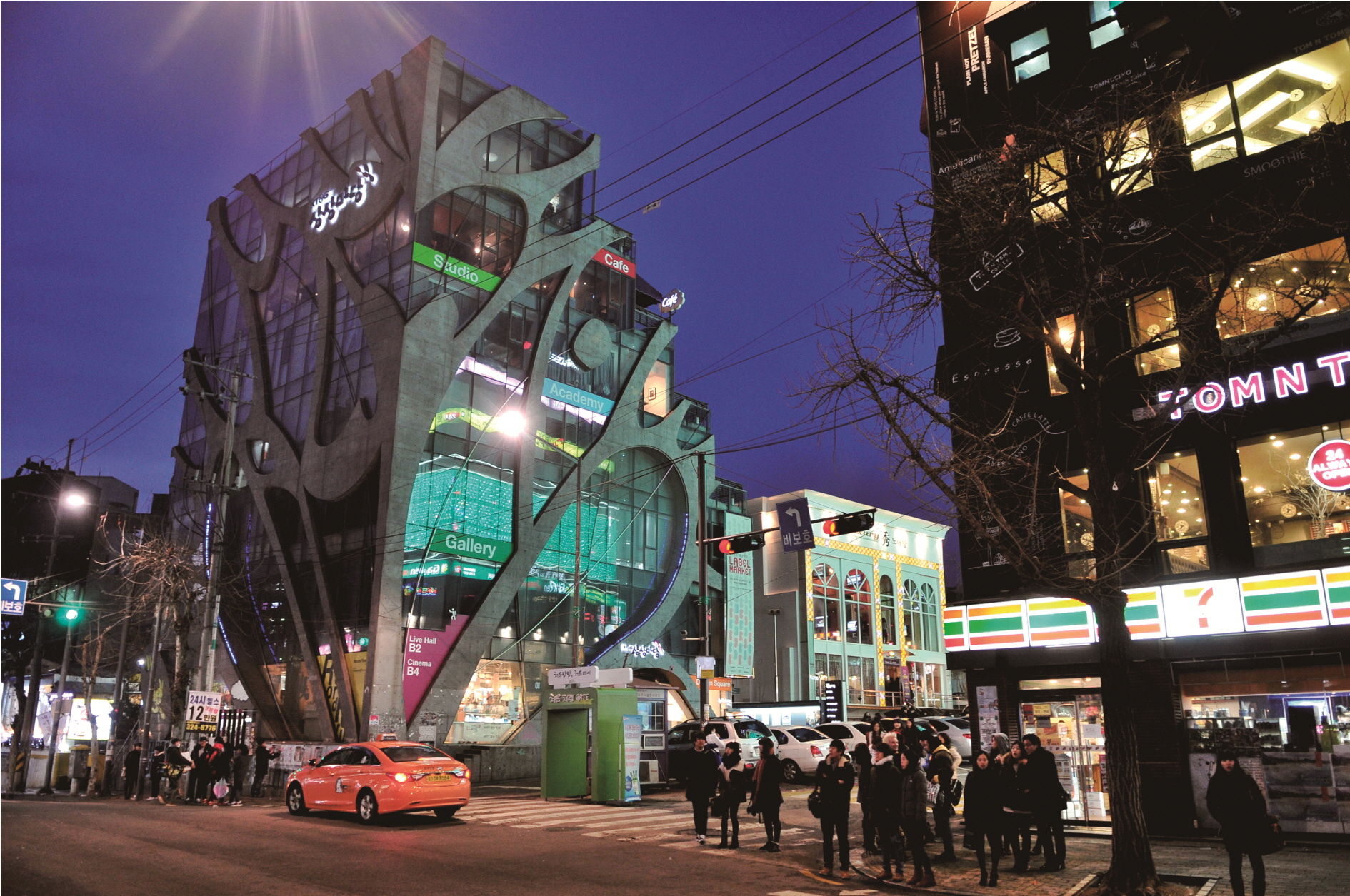

The Dong-A Ilbo, one of Korea’s largest newspapers, recently relayed the tale of Mr. Lee, a shy 28-year-old man who, at first glance, seems to be living the dream. He’s got three girlfriends— one is an English instructor at a kindergarten, one is a graduate student studying art, and the other works at a foreign financial firm. All of them look like models. He takes them out to clubs, art galleries, and film sets, depending on what each one is into.

There’s just one catch—none of these girlfriends are real. They are online personalities Lee met through a cyber dating service. The women at the service look and act like real girlfriends whose moods change depending on the date location and topic of conversation. The service uses lesser known actors for its video services. And business is good— about 40,000 users signed up within just 10 days of the service’s launch. About 80% of them are men in their 20s and 30s.

At Afreeca, a popular personal Internet TV site, there are men spending hundreds of thousands of won for online women to call out their online nicknames on their video channels. These “BJs” (broadcasting jockeys) earn their keep by getting men to send them “star balloons,” online tokens that cost 70 won each. The most popular women can earn millions of won a night. One of the best has 50 million viewers.

The smartphone has also made online “dating” easier. Korean app developers have come up with many adroit messaging apps with which the lonely can connect with members of the opposite sex, real or not. Apps like Doki Doki Postbox, Whispering Sailors, and Fav Talk bill themselves as online pen pal services connecting users with similar interests such as K-pop, but in fact, the desperate use these to communicate with multiple members of the opposite sex. This has also led, unfortunately, to the appearance of cyber con artists who make their living financially exploiting lonely men online.

Enter the Herbivores | 초식남

Why is it that more and more men are avoiding real-world relationships with the opposite sex in favor of online relationships?

According to experts, this is connected with the rise in Korea of the chosiknam, or “herbivore man.” The term was first coined about 10 years ago in Japan, where this phenomenon first appeared. Tired of the uber-competitive nature of Japanese society, where men were expected, in the words of Slate’s Alexandra Harney, to “live like characters on Mad Men, chasing secretaries, drinking with the boys, and splurging on watches, golf, and new cars,” the bulk of Japan’s young manhood decided to opt out to pursue their own hobbies and, more importantly, not pursue women. Instead, they found their satisfaction elsewhere, such as anime and pornography. Japan’s political and media establishment was horrified, blaming the trend for Japan’s plummeting birth rates.

It wasn’t long before this trend arrived on Korean shores. As in Japan, Korea’s herbivore men are the product of Korean society’s notorious competitiveness, especially in the dating market, where women value—some argue excessively—a man’s job, education, and family background above all else. Feeling unable or unwilling to play the game, many men are opting out, content to pursue online sources of romantic satisfaction. Some would be unable to perform even if they found themselves with a member of the opposite sex—in 2009, at the start of this phenomenon, a urologist wrote in the Weekly Dong-A magazine that more and more men in their 20s were suffering from sexual dysfunction that presented itself only—oddly enough—-when they were in the presence of a woman.

Korea’s gender imbalance plays a role, too. As of 2010, there were 113.7 men for every 100 women in the 20–24 age bracket. For those aged 25–29, there were 103.8 men for every 100 women, and for those aged 30–34, there were 102.0 men for every 100 women. As if the

dating market weren’t tough enough.

Dried Fish Women | 건어물녀

Women, too, are experiencing romantic—or unromantic, as it were— trends of their own. As more and more women rise to prominence in the workforce, some are abandoning love and marriage all together to focus on their careers. These women are called “dried fish women,” or geoneomulnyeo. Like the herbivore man, it’s a term that came from Japan, where this trend began. Polite, smartly dressed, and good at their jobs, they let themselves go on the weekend, too tired to dress up, clean their home, or go out. Content with a can of beer and some dried fish snacks, the love of their lives is most often their pets. When they’re not sleeping, they can be found watching TV or reading comics. If these women marry, it is often in their late 30s.

Suffice it to say, neither of these trends have helped Korea’s birthrate, which—despite impressive improvements over the last three years—is still one of the lowest in the world. A 2011 poll by international pharmaceutical firm Eli Lilly found Korean couples were the least sexually active in the world. With young men and women now swearing one another off, it does not bode well for the future of Korea’s aging society.

Written by Robert Koehler