Abuses of system prompt immigration authorities to act

On April 24, the Korean daily Dong-A Ilbo broke news that Korea’s immigration authorities were planning to revise Korea’s immigration laws to ban Koreans who make under KRW 1.12 million a month from marrying a foreigner. Or, to be more precise, it would stop immigration authorities from issuing marriage immigrant visas to the prospective immigrant spouses of those making less than 120% of the minimum cost of living and those receiving support under the National Basic Livelihood Act. Authorities are even considering a plan to raise the minimum income level needed to receive a marriage immigrant visa to 80% of the minimum cost of living.

Since 2006, when the number of so-called international marriages peaked at 38,759, international marriages have been on a downward trajectory, with just 28,326 international marriages performed in 2012. The divorce rate, however, has continued to hold more or less steady at an uncomfortably high rate—in 2013, 10,887 international marriages broke apart. With an endless stream of horror stories of spousal abuse, scam marriages, broken families, and other abuses of the system, the government is finally moving to reform the system. The question is, will it be enough?

Beating the brokers

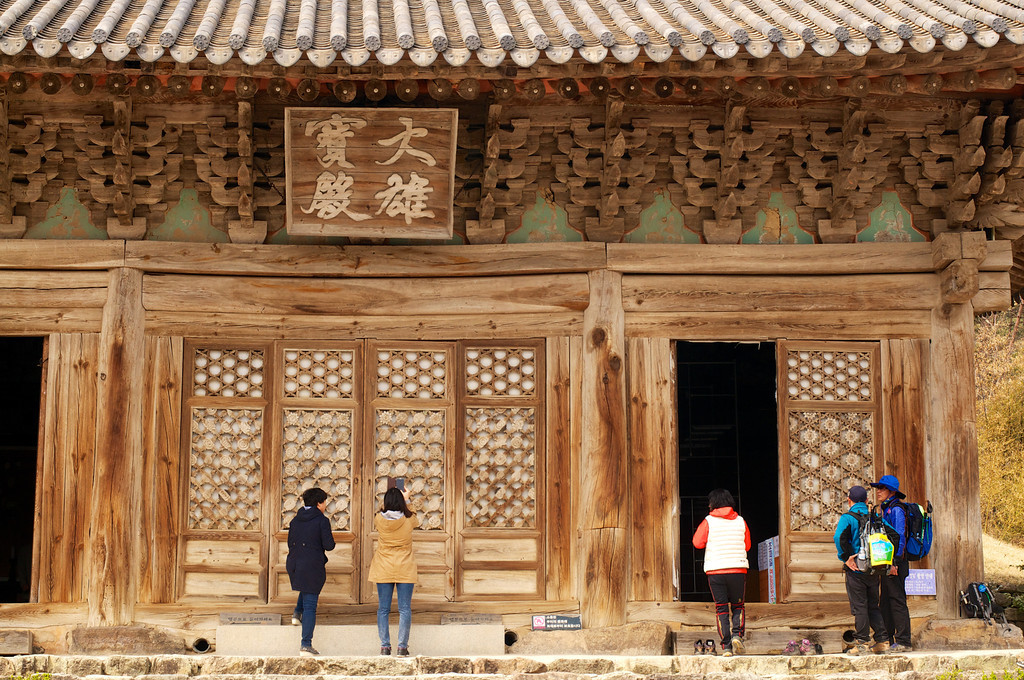

International marriage is not new to Korea. According to the 13th century history textbook Samguk Yusa, King Suro of the southern Korean kingdom Geumgwan Gaya in the second century married a northern Indian princess who sailed all the way from the subcontinent to Korea. King Gongmin of the Goryeo Dynasty was married to a Mongolian princess, as was the practice of kings of the latter part of the Goryeo Dynasty. Even Korea’s first president Syngman Rhee married Austrian Franziska Donner, who accordingly became Korea’s first First Lady.

Still, international marriages tended to be rare, especially in the modern era. Things began to change from the early 1990s, when women—largely ethnic Koreans from China and Southeast Asians—began coming to Korea to marry mostly rural men. The trend accelerated in the subsequent decade. By 2005, more than 40% of rural bachelors were marrying foreign women. Worried about the decreasing and increasingly elderly population, local authorities even encouraged the process by providing subsidies to international couples.

The trend was not without serious problems, though. Many of these marriages ended in failure due to cultural differences and communication barriers—not surprising, considering that many of these marriages were concluded within just a couple of days of getting introduced by brokers that prioritized profits over love. Some foreign women were duped into marrying mentally ill and/or abusive men; some wives were even killed by their husbands. Some foreign women used the system as a means to illegally immigrate to Korea, disappearing soon after their arrival and leaving their husbands heartbroken. There were plenty of sham marriages, too, in which men in need of cash “married” women wanting to come to Korea as part of a visa scam. The situation got so bad that at one point in 2010, the Cambodian government temporarily banned local women from marrying Korean men met through matchmaking brokers. Vietnam, too, banned young women from marrying Korean men over the age of 50. Hanoi also barred marriages between Korean men and Vietnamese women separated by more than 16 years of age.

Perhaps as intended, strengthened regulations have taken a toll on the matchmaking industry. According to the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, the number of international marriage matchmaking companies dropped from 1,390 at the end of last year to 1,276 at the end of March, a reduction of 6.9% in just three months.

Not just Korea

Korea’s regulatory revisions, if they go into effect, would affect not only low-income Koreans. The government will not give out marriage immigrant visas to Korean men lacking a stable place to live. This means Korean men living in motels or gosiwon (one-room apartments usually used by young working people) may not be issued marriage visas for their brides, nor might those living with a third person who is not a relative. Likewise, those men who have recently entered into a previous international marriage and gotten divorced will be banned from entering into another one right away. Other measures are under consideration, too, including a plan to make it mandatory for prospective foreign wives to pass Level 1 of the Test of Proficiency in Korean before they are given a marriage visa; if they fail, their visa issuance is delayed six months. Fail it twice, and they’ll need to take a government-mandated social integration class when they come to Korea. Couples who can communicate in a third language, such as English, would be excluded.

Korea is not the only country with such regulations on the books. The United States, for instance, grants marriage visas for foreign spouses only to those who make 125% of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) poverty guidelines. The United Kingdom, too, has a £18,600 income requirement, and you must be able to accommodate yourself and your dependents without recourse to public funds.

Written by Robert Koehler