©Yonhap News

Ubiquitous, brightly lit and loved by the locals, convenience stores are integral to the Seoul experience. A few big brands control a multi-billion-won market that caters to changing lifestyles. We look into the reasons behind the success of this gigantic industry.

It’s nearly eight o’clock when Lee Seung-hwan appears in front of the shop, dressed in office attire with headphones attached to his ears. The 29-year-old claims assistant just left his desk at an insurance company in nearby Gangnam to follow his dinner routine: buying a packet of ready-made ramen at a convenience store. “My eating pattern is irregular. I mostly eat alone, but sometimes I have to take my dinner at the office. Buying food here allows for more flexibility.”

©Yonhap News

Lee likes the convenience of this particular GS25 store, which lays midway between the nearest metro station and his studio in the Nakseongdae neighbourhood of Seoul. But it is not his only motive to frequent convenience stores. “The choice of fresh food is actually quite good,” Lee says. “It is easy. I only need to heat this for a few minutes before I can eat it at home.”

Watching from the terrace in front of the store that evening we saw a steady stream of tired-looking employees coming in to buy their dinner. Consumers in South Korea have largely adopted the convenience store model of ready-made, single portion meals that is contributing to the spectacular growth of the sector in the country. Over the past ten years the number of stores has grown from 10,000 to a staggering 35,000, making the brightly lit shops a defining feature of the Korean urban landscape. Last year the three main convenience store brands, CU, GS25 and 7-Eleven achieved a landmark result: their combined revenue of KRW 14.25 trillion (US$12.61 billion) surpassed that of the top 3 department stores – Hyundai, Shinsegae and Lotte.

The success of the convenience stores might seem strange at first. They provide a convenient alternative to supermarkets but offer far fewer items in comparison. The food they sell might be fresh, but is not what most people would identify as haute-cuisine. Importantly, almost all items sold at convenience stores are more expensive than in regular shops. How is it then that convenience stores have become so successful?

The single factor

Ask Lee about it and he points to the buildings adjacent to the shop. There are a lot of studios for single households in Nakseongdae, he says. For their inhabitants, the convenience store is exactly what they need. He himself visits such stores about twenty times a week, by his own estimate. “I live alone and do not need a lot of food,” he says. “I never go to the supermarket. Bigger supplies I buy online, and for fresh food I use the convenience stores.”

©Dylan Goldby

Latest figures show that more and more people are living alone in Korea. According to Statistics Korea, the number of single-member households has grown to 5.2 million, totaling more than a quarter of all households nationwide. The trend of doing things such as eating, drinking and shopping alone has sprung up, as the August edition of SEOUL Magazine discussed.

“Shopping was a family affair in the past, but people do that alone nowadays,” says Yoon Dae-jin, a data analyst working at the investor relations team of BGF Retail, the company behind CU. The old pattern of buying groceries in bulk at supermarkets is slowly waning. “Customers find it time-consuming, and it leads to waste because people buy more than they need. At a convenience store, they have the impression of being in control of their spending. Whereas the average spending per visit at supermarkets is situated around KRW 50,000, it falls down to around KRW 5,000 at convenience stores.”

Minimum wage, maximal growth

CU is headquartered in an unassuming brick building on a six-lane Gangnam avenue. As everybody else inside the building, Yoon wears the company’s uniform, a unisex grey vest that inevitably brings to mind a sales clerk outfit. He escorts us to the basement, which is divided into countless smaller glass cubicles. “Here, we welcome prospective shop-owners,” Yoon says. “We discuss their business plan and explain them how the job works.”

Convenience store companies are able to rapidly expand their footprint through the use of the franchise model. Yoon explains that most shop owners are self-employed but that they have a contractual engagement regulating everything from opening hours (preferably 24/7) to, of course, the share of profit they will send monthly to headquarters.

The power relationship between big companies and shop owners is obviously one-sided. An outcry in 2013 following the suicide of a CU shop owner and the tampering of the death certificate by the company shed some light on their harsh working conditions. Impossible profit targets and high penalties in case of advanced closure were especially pointed at.

@Yonhap News

The situation of convenience store employees is another contentious factor behind the success of the industry. The pressure to be open 24/7 means that the sector heavily relies on part-time workers to run their shops at night and during holidays. The unemployed, students and others in search of a “day job” that will almost always happen at night form a seemingly inexhaustible pool of willing part-timers. Hyper-flexibility is a standard expectation here, while the minimum wage is the norm – after a more than 15 percent rise, it is set for next year at KRW 7,530 per hour (US$6.62).

Clearly problematic for older workers and employees with children, the flexibility of the position can appeal to a younger crowd. “I am doing this to save money before going to the military” says 19-year-old Chun Oh-Min from behind his counter at another store. “I live at my parents’ and I do not have any fixed expenses. The money I am making will help me later for my studies.”

Tricks of the trade

It is getting late, and we feel hungry after our talk with Chun. He pauses when we put our food boxes on the counter, discretely glancing at us before typing on his keyboard. Is he trying to guess our ages?

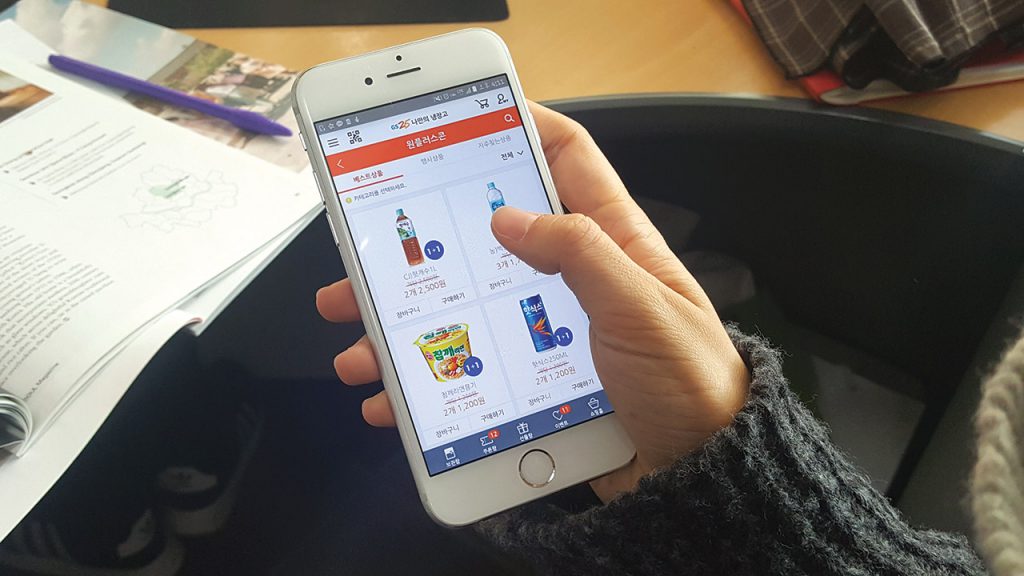

Data collection is central to the business model of the industry. Credit cards and loyalty programs ensure that brands know who buys what, at what time and in what quantity. Employees are instructed to input gender, age category and nationality (Korean or foreigner) at the till for each cash payment. Apps such as My Own Refrigerator by GS25 go a step further by proposing tailor-made promotions to customers on their favourite range of products. Brands rely on this ever-refined data analysis to stay in tune – or even dictate – consuming patterns.

Vying to differentiate themselves from competitors, store chains also heavily compete in the development of original products. Some patrons seem to love it: a quick research on the internet shows that there is a fan-base for specific convenience store food, and a few snacks or beverages have become collector items (see box on page 19). Brands are also careful to appear in touch with their customers’ daily life. During the recent Chuseok holidays, several brands proposed specifically themed meal boxes with “home-cooked style dishes” and the traditional songpyeon rice cake.

©Yonhap News

Successive years of double-digit growth in the sector have sharpened the appetite of big chains, which are all bolstering the scope of services they offer. Banking kiosks are becoming a frequent occurrence in convenience stores, and most chains offer mail delivery systems where customers can have their parcels sent to their local stores and pick them up at their chosen time. Challenging CU and GS25, the two dominant players of the field, 7-Eleven (affiliated with Lotte) and the relative newcomer Emart24 (owned by Shinsegae) are willing to experiment more with their in-store concepts. They propose a wider array of services ranging from laundromats to coffee shops to libraries.

From trend to lifestyle

The blend of attentive data analysis, service diversification and positive customer response has installed convenience stores as a central feature of urban life in the country. Much more than simple block stores, their status is fast elevating to that of a part-time concierge or personal assistant who takes care of the food, collects the mail and attends to an ever-growing list of other services.

©Yonhap News

The unique position of convenience stores in Korea is further reflected in how customers take advantage of their seating facilities. Stores are increasingly popular meeting places where couples have a beer, business is discussed and, thanks to the many terraces attached to the shops, patrons enjoy a party. We meet Ji-hyeon and her friends outside a store in Gyeongnidan on a late-summer night. Seated around a plastic table cluttered with paper cups and empty wine bottles, their back to trash bins where surrounding diners regularly empty leftovers, the four fashion design students seem indifferent to the no-frills decor. “Bars are too expensive for us. But who needs a bar when you have this?” they say, gesturing at the busy terrace around us.

©Dylan Goldby

Ji-hyeon, who traveled an hour by bus to get here, explains how she and other cash-strapped students like her use in various ways the communal spaces convenience stores offer. “This kind of terrace is a perfect place to hang out. The atmosphere of this neighbourhood is viral, and it is almost like you are drinking in the street” she enthuses.

Partying is one thing, but could she use a convenience store for a date? “I have actually done it. It is nice. The food is usually pretty good.” At this point we look at her three friends, trying to make sure that we are not being taken for a ride. All look at her approvingly. If they are good enough for a date, there definitely is a future for convenience stores in this country.

©Hwang Sun-young

More About Convenience Stores…

Five not to miss

Convenience store companies are engaged in a frenetic race to find new avenues of growth. Some brands are partnering with existing venues. CU runs a shop on the first floor of a noraebang in Hongdae, where customers will find specifically themed items. Emart24, a latecomer convenience store brand, recently opened a shop at Seoul Arts Center where customers can listen to high-quality classical music. Others bet on technology. 7-Eleven recently opened an unmanned “smart store” in the Lotte Tower in Jamsil. Pre-registered customers load their items on a self-scanning conveyor belt once their shopping is done, and they checkout by scanning the palm of their hand, linked to their credit card by a “bio pay” system.

©Yonhap News

Some favorite convenience stores stick out not because of their innovative concept, but simply because their shape or location is unique. Take a look at the matchbox-like GS25 in Olympic Park for example, or the “convenience store with a view” right at the beginning of Suseongdong Valley. From the terrace you will have an imposing view of Inwangsan Mountain.

Cult status

Because of the high turnover in convenience store products, customers often have to say goodbye to favorite items. This sometimes leads to a lively online trade long after the items have disappeared from shelves. Specific items have achieved cult status, such as GS25’s “Minions Milk” sold in specially designed bottles covered with the popular animation figure. At their peak, the chain was selling more than 100,000 milk bottles a day.

Stores of Seoul (@stores_of_seoul)

Intrigued by the impact of convenience stores on the city’s urban landscape, the authors of this article have opened “Store of Seoul,” an Instagram account conceived as a collaborative platform. Send us your best shots of big, small, slick, grubby, weird or just beautiful exteriors of convenience stores along with their exact location by email on storesofseoul@gmail.com or directly via Instagram @stores_of_seoul. We will share the best shots.

©Yonhap News

Written by Hadrien Diez & Jeroen Visser