BookGoodCome’s Rury Lee moves young hearts through children’s literature

Ask Rury Lee, the editor-in-chief at publishing house BookGoodCome – a clever play on the Korean word for polar bear, bukgeukgom – about his interest in bears, and he’ll smile and tell you it’s because he resembles a bear himself. With his transparent round glasses and white scarf, the rosy cheeked author of the award-winning children’s book “Coda the Bear” could win a Santa Claus look-alike competition. Jovial and young in spirit, he is what you might expect from one of Korea’s best known children’s writers.

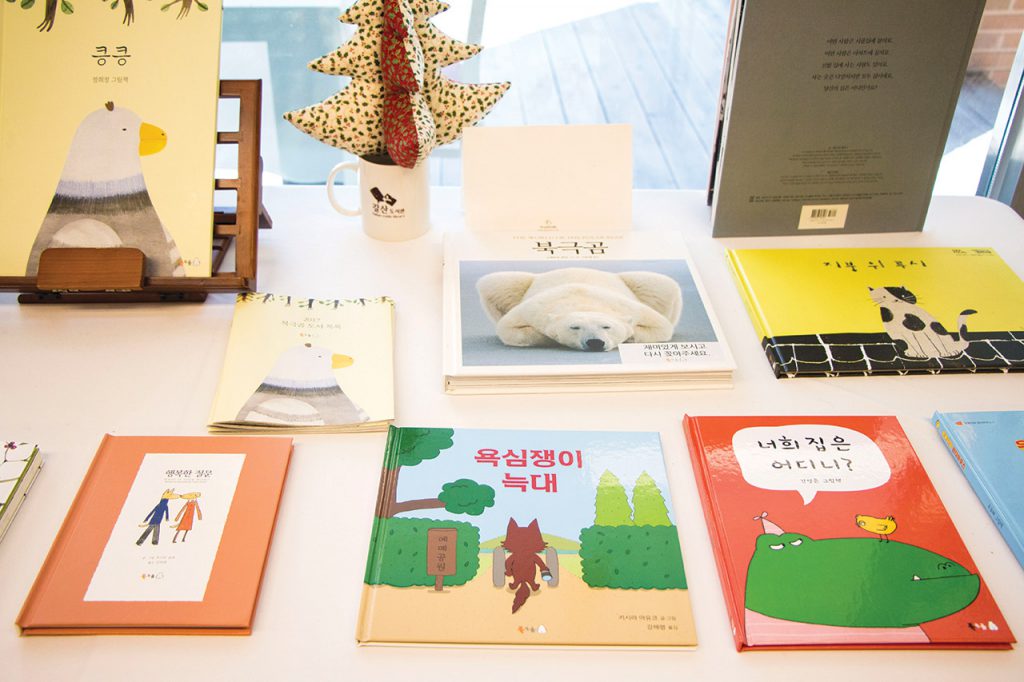

Focusing on children’s books and picture books, BookGoodCome imports and translates popular titles in addition to translating and exporting Korean stories to other countries. To Lee, the picture book is no infantile pursuit. Or at least it doesn’t have to be. “A great picture book is like any other great piece of artwork,” he says. “It has to grab people emotionally.”

A childhood without childhood books

“When I was a child, there weren’t many opportunities to read children’s books,” Lee recalls. “I had two older brothers, six and eight years my senior. Since my parents didn’t expect to have a third child, they got rid of a lot of books before I was born.”

Nevertheless, his older brothers encouraged his love of literature. He says, “When I was in fifth grade, my brother, then a high school student, read Ernest Hemingway’s ‘Farewell to Arms’ to me, from start to finish.” The book was far too difficult for a fifth grader; it felt like torture until he started getting into the story. Afterwards, his brother began recommending titles for Lee to buy from a nearby used bookstore. “I would buy a book from the store, read it, sell it back and buy another book,” he says.

Driven to write

As he discovered literature, he also found he wanted to become a writer. Before that, he’d wanted to become a doctor and save lives, but his father warned him that the family was too poor to send him to medical school. Lee wondered, “What could I do to save lives that didn’t involve going to college?” He realized that many writers didn’t have an academic background. “More importantly, I began to realize that the arts were about an eternal life,” he says. “Not only do people have physical bodies, but also souls. I learned that if doctors save physical bodies, maybe writers can save souls.”

He remembers the joy of journaling in elementary school. He recalls winning a writing competition with a poem about traditional palaces, which encouraged him to write more and enter more competitions. He says, “Even at a young age, I was thinking about what makes a good book and how to become a good writer.”

A great picture book

Despite his family’s financial difficulties, Lee eventually attended Korea University, one of the country’s most prestigious schools, earning the money needed for tuition himself. Developing an interest in German culture, Lee studied German. After graduating in 1998, he ended up teaching a course on children’s books and writing. That’s when he found his love of picture books. “I’d always thought that picture books were for children,” he explains. Then he came across John Burningham’s “The Boy Who Was Always Late.” He found the imaginative story entrancing. “I’d expected the story to teach me some kind of lesson,” he recounts. “But it wasn’t like that at all. I didn’t know how to interpret the moral of that story at all!”

Reading one title after another, he discovered the entirely new world of picture books. “I came to understand picture books as an artistic genre. What’s more, that understanding wasn’t limited to picture books, but also included children’s books.”

Finding it difficult to share his newfound passion with his peers, Lee began to write reviews of children’s books for the Hankyoreh, a Korean newspaper. He says that his goal was, and still is, to promote books that can touch people. “Personally, I think that works [that touch people] tend to be funny or sad. You’d be surprised how funny a work can be, or how a sad work can warm your heart.” Although Lee recognizes that the genre of children’s books is widening, he hopes to see more works that focus on fun instead of teaching lessons to the readers.

Dreams come true

Lee’s reviews began to get some exposure. He even found a few like-minded friends, one of whom suggested that he start translating. His first translation was published in 2003 under his then newly minted pen name, Rury. “In Korea, Rury means to make your dreams come true,” he explains. By translating several hit books, Lee got his footing as a translator. He’d yet to write his own stories, however.

After getting married, he made a resolution. “For 40 years, I’d been doing the kind of work that I needed to make money, even if I didn’t want to do it,” Lee recalls. Since he and his wife, who is now BookGoodCome’s CEO, married quite late, they didn’t want to waste any more time. “I’d only dipped one foot into my true calling. For the rest of my life, I was going to pursue what I love.”

BookGoodCome was founded in 2009, when he published his first book, “Black Noses,” or “Coda the Polar Bear,” the first book in the “Black Noses” series. Since the book was so well received in Korea, they marketed the book to several other publishers at an international book fair in Bologna. Today, there are seven versions of “Black Noses” available, and Lee continues to write.

To be continued

Not only has Lee promoted his own books through BookGoodCome, the company has helped to promote Korea’s children literature as a genre internationally. Some of their bestsellers include, “The Warm Breath,” “Whale Rock” and “Teddy, Are You Alright?” He also teaches classes, holds writing workshops and reads children’s books at schools. Attending international book fairs twice a year, Lee is constantly scouring for new titles to translate into Korean.

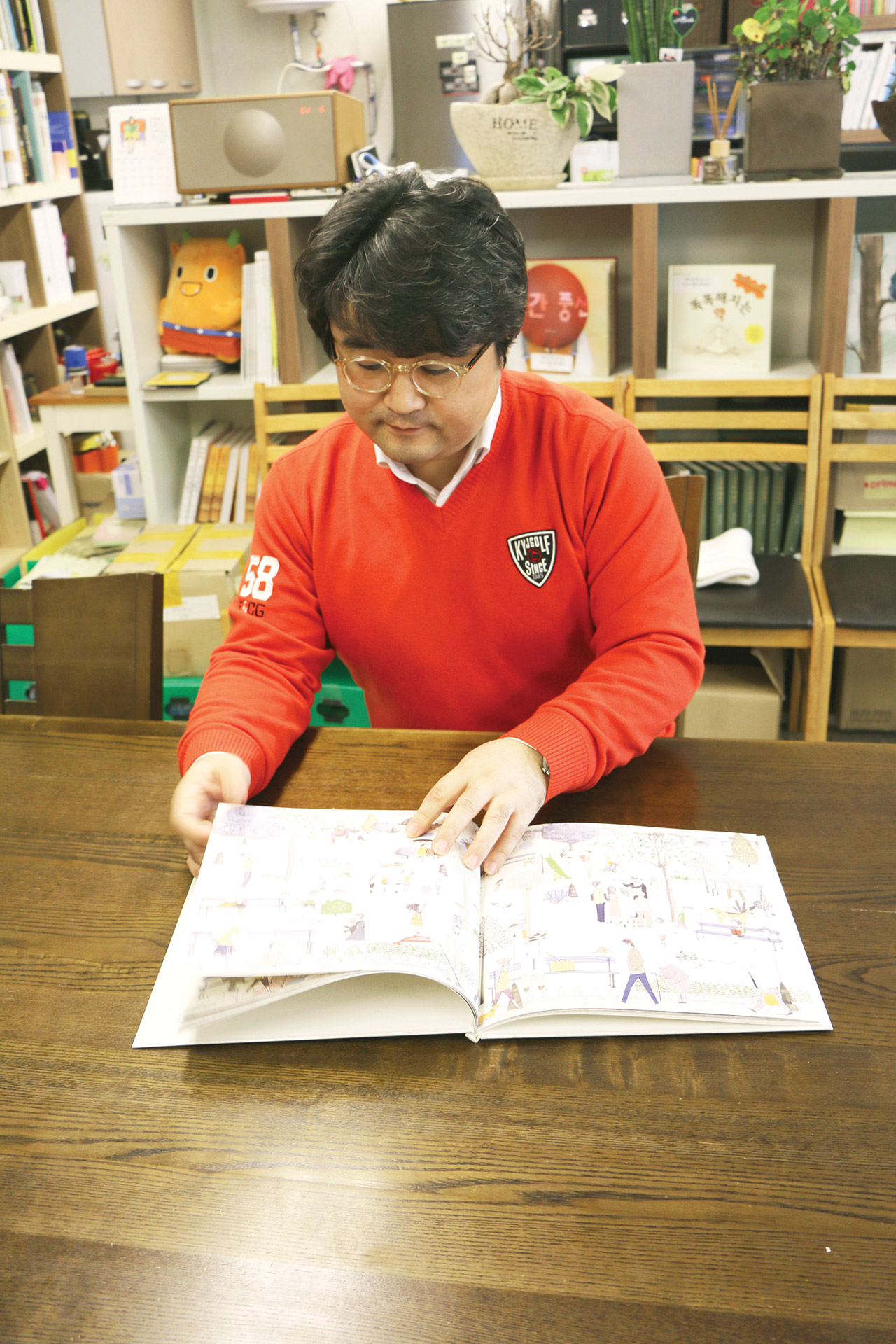

What’s more, he continues to be moved by children’s books all the time. “The message of a book is something that the reader discovers through his or her life experiences. Interpreting that message is to find the real meaning of the book,” Lee says, minutes before leafing through the Korean version of the “El Arenque Rojo.” Written by Gonzalo Moure and illustrated by Alicia Varela, it’s a “picture book without text,” and Lee narrates the story aloud. “What a beautiful book,” Lee says. It’s as if he’s reading for the first time once again.

More Info

bookgoodcome.com

bookgoodcome@gmail.com

Written by Hahna Yoon

Photography by Diana Park