Silver inlay master Hong Jeong-sil always keeps things in perspective

Anyone who has seen metalwork from Korea’s ancient times probably knows that they were made with great care and skill by people who’ve spent entire lifetimes perfecting their art. Candlesticks, incense holders and burners, metal jars and all sorts of cases of both ceremonial and practical purpose – such figments from the past indicate the artisanal mastery of craftspeople who turned otherwise ordinary objects into representations of immortal beauty.

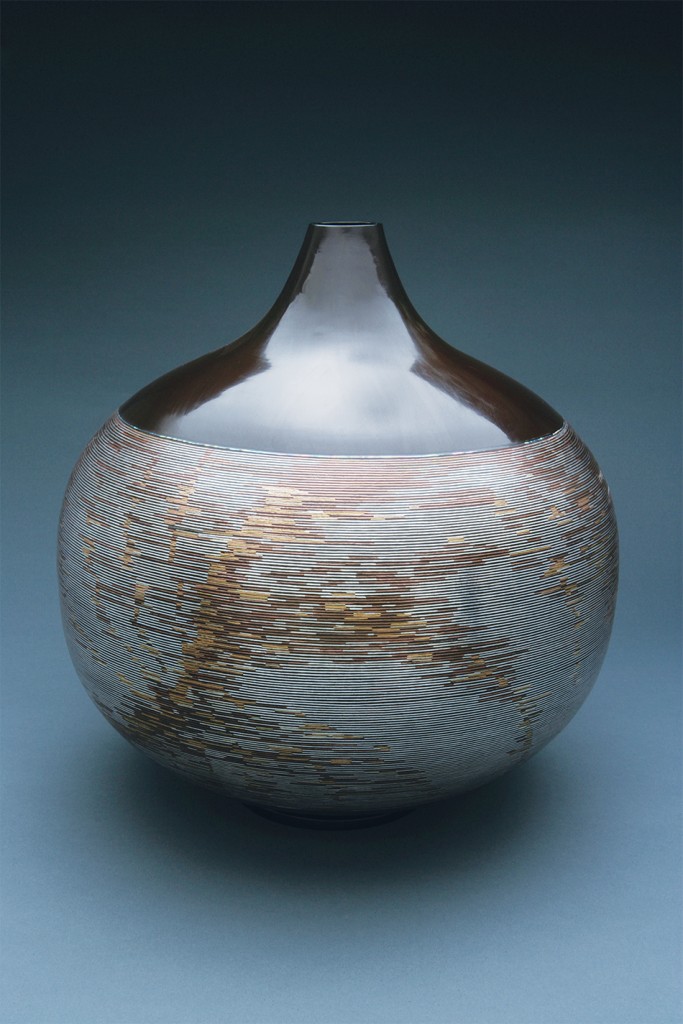

Hong Jeong-sil is a master craftswoman who specializes in silver inlaying, which involves meticulously hammering, stenciling and chiseling individual threads of silver, gold and other precious metals onto metalwork surfaces, forming exquisitely decorative patterns. Although silver inlaying thrived during the Goryeo Kingdom (918-1392) and then extended into Joseon Dynasty times (1392-1910), she has revived and modernized the craft, and is the foremost living authority on the subject. Yet she wasn’t always such an adamant devotee of Korea’s traditional arts. She studied modern craft arts as a university student, and only learned about traditional silver inlay work, known as ipsa, while perusing a book about her ancestors’ crafts and the people who keep them alive today. The book, titled “Inganmunhwajae,” or “Human Cultural Properties,” described ipsa as a dying art, with only a few practitioners left. What stirred something in Hong’s heart, though, was the book’s claim that whoever learned and continued ipsa would be doing a great service in the name of the country’s precious cultural heritage.

A personal assignment

“It was almost like the book was assigning me a mission,” Hong recalls. After completing her studies, Hong set out to fulfill that mission. At first she studied under a master sculptor, but eventually found one of the sole remaining ipsa masters, Lee Hak-eung – after five years of searching. Lee was 80 at the time, and hadn’t actively practiced his craft for 20 years. Fortunately, he was charmed by Hong’s sincerity and dedication, especially since ipsa was on the verge of extinction. Lee gladly accepted her as his disciple and began instructing her in the art’s principles and practices.

While absorbing as much as her mentor could teach, Hong eventually realized that ipsa needed to be officially recognized by the government if it were to truly flourish. After collecting all the relevant data she could find, personally documenting and photographing each individual piece she discovered, Hong filed a report that explained the basics of ipsa and stressed its importance. Thanks to her report, ipsa was registered as an important intangible cultural property in 1983. Hong continued to perfect her skills under Lee, and eventually established her own school for instructing aspiring artisans. After her mentor’s death in 1988, she was made the official holder of ipsa in 1996. Two years later, she compiled her findings and knowledge into a book that detailed the processes and tools of her trade. She has almost single-handedly revived what was once an obscure ancient art form that was slipping into memory.

Starting from scratch

Although the average viewer is likely to acknowledge the beauty of ipsa’s intricate patterns, few are actually aware of how much work and time goes into applying them. Everything is done by hand, including the manipulation and refinement of the gold or silver into fine strands. Over 30 different types of tools – chisels, hammers, tweezers, pliers – line the walls and shelves of Hong’s office. Patterns must first be carefully drawn out and stenciled to perfection before the inlay process can begin. Each strand must be applied individually, meaning even a simple line or curve requires hours of work.

“The hardest part about learning everything was the lack of ‘curriculum,’ so to speak, because there was so little information available about ipsa at the time. Nobody had really researched it because hardly anyone even knew about it,” Hong says. “It had basically been abandoned.”

Born in Pyeongyang in 1947, Hong has witnessed many shifts amid Korea’s rapid and often chaotic transformation from a former Japanese colony – poor, battered and culturally confused – into one of the world’s largest economies. Hong’s interests, by contrast, have stayed surprisingly consistent. She says she was always interested in “making beautiful things,” and that it was no question for her to study the arts, be they modern or ancient, native or foreign. In fact, her explorations of modern jewelry design and the traditional crafts of other nations, such as India and China, have inspired her to ask the question: What is the Korean sense of beauty?

“Some people despair at the disposal of traditional culture that occurred throughout Korea’s often rushed modernization,” says Hong, “but I think it couldn’t have been any other way. Only now can we afford to look back and reflect on what can be learned from our past, on what can be salvaged. Only now do we have the economic status that affords us the ability to value our traditional culture.” Hong thinks that people don’t like Italian fashion, German design or French paintings simply because of an object’s beauty or quality; everything’s dependent on a country’s ability to enforce its image onto the world screen. “Korea’s culture and traditional arts are getting more attention these days, not because they’ve gotten better or more beautiful – they’ve always been beautiful – but because people’s perceptions have changed,” she says. “Korea’s original sense of beauty, something only we can intuitively know, is finally getting some attention.”

‘Korea’s original sense of beauty, something only we can intuitively know, is finally getting some attention.’

Changing perspectives

Perceptions have indeed changed. Never before has Korean culture received so much international exposure – whether it’s K-pop, films, literature or television – and art is no exception. Although she started out doing something even her own compatriots didn’t know about, Hong’s work is now displayed in exhibitions, museums and galleries across the world. Last year, her work was featured in Milan at an exhibition titled “Constancy and Change in Korean Traditional Craft,” an exclusive event that featured only an elite handful of artists. To Hong, who considers herself an educator as well as an artisan, letting people know about her work is almost as important as personal expertise. “If people don’t know about it, then it won’t stay alive,” she says. “You can’t keep something alive simply by being very good at it, because then it ends with you. You have to let people know; you have to show them.”

Now that she’s established and in her 60s, Hong’s main goal is to educate people, particularly young Koreans, about the value of native crafts and why they need to be continued. She still teaches, and is always trying to think up new ways to change people’s perception of traditional crafts.

“Tradition and modernity, past and present, aren’t separated by some boundary like some people think. They are inevitably linked,” she says. “The past isn’t over; it illuminates the present and helps reveal the future.”

Written by Felix Im

Photographed by RAUM