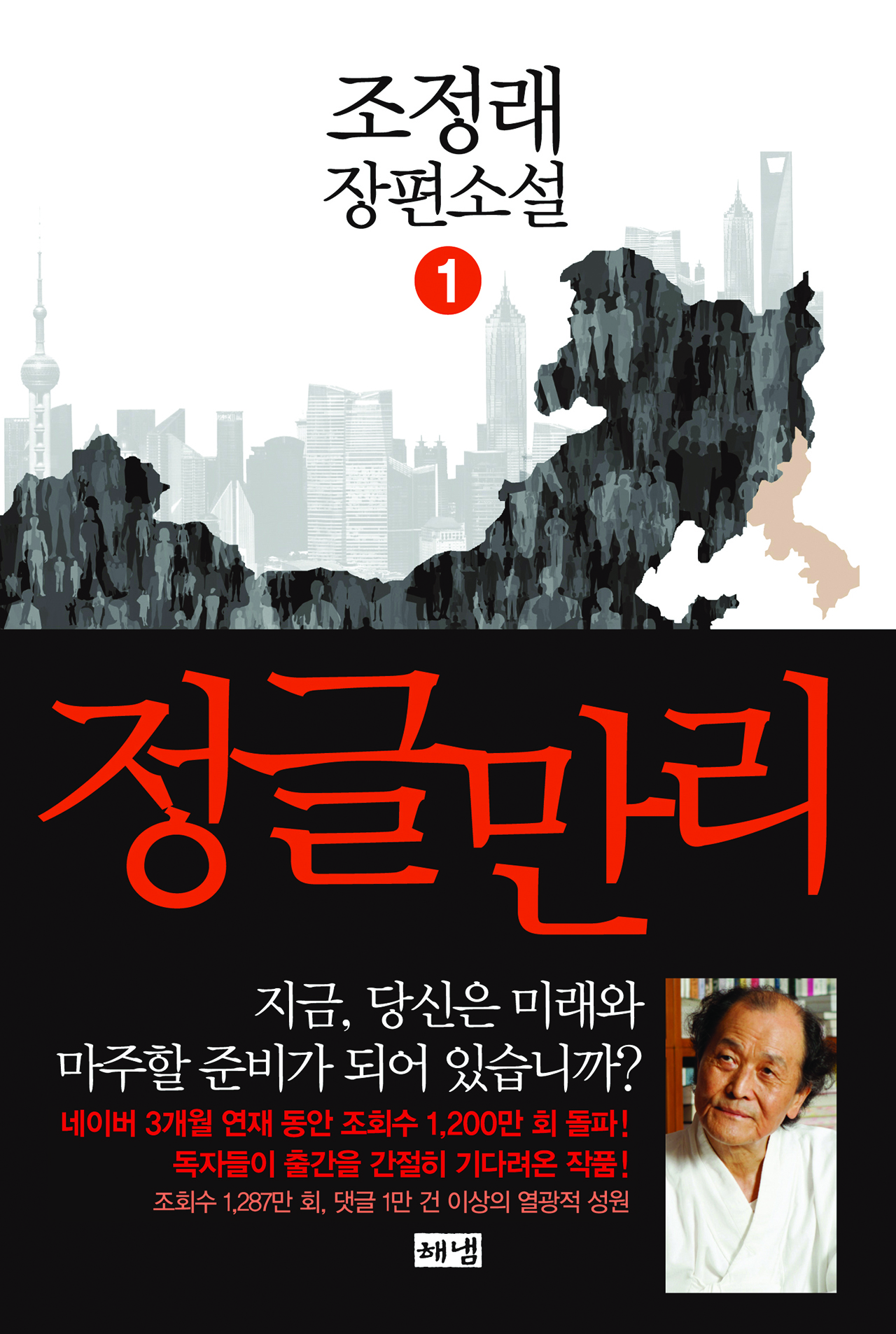

Veteran Korean novelist Jo Jung-Rae’s ‘The Human Jungle’ is a critical look at a rising world power

With the recent arrival of a group of younger, primarily female Korean writers to the international scene, it easy to overlook a group of older writers who have been writing away for decades with considerable success. Jo Jung-Rae is one of these authors, and his “The Human Jungle” (Chin Music Press), written in 2014, has now been released in English translation. “The Human Jungle” does something unusual for Korean literature, and takes place outside of Korea and includes an international cast of widely disparate characters. Jo has little mercy on any of those characters. Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and French protagonists are all united in the desire to participate in the economic bonanza that they see in China, and Jo portrays them with a harshly satirical eye.

The story opens with a semi-stock Korean character, a man banished from his country. Doctor So Hawon has botched a plastic surgery in Korea and been forced to flee. His first day in China is frenetic, complete with his car getting involved in an accident with a bicyclist that his friend Chon Taegwang correctly diagnoses as an insurance shakedown. This sets the jungle-like tone for the book; most of the characters are ruthlessly out for themselves and happy to use guanxi (personal relationships), backstabbing and insider information to achieve their aims. A key concept in the story is the common phrase ren tai duo, which literally translates to “too many people,” but also has the implication “three hundred million of you ought to drop dead.” It is in this environment that the protagonists find opportunity and danger. Some Korean characters come across as pollyannaish, but Jo does a good job of embedding satirical takes on Korea in the words he places in the mouths of Korean characters when they assess Chinese society. In a Shakespearean sense Korean characters “doth protest too much,” and reveal themselves in that way.

The book hops across China, as do the interweaving plots. The scope of the story is hinted at by the cast of characters list at the start of the book, which runs to some 40 people. It is a testament to Jo’s skill – and that of translators Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton – that it is rarely difficult to keep track of all these characters and that they stand alone as identifiable and separate personalities. Jo has an occasional tendency to data-dump, apparently eager to demonstrate his broad knowledge of China, but this is mostly kept in check by the propulsion of the plot. Jo’s writing is not ornate – it is blunt and plainly descriptive, as in most of his other works. But the plot keeps moving, and when the book ends, despite it’s length, you may find yourselves wishing for a sequel that further traces the lives of Jo’s characters. That is a testament to how interesting the book is and how well Jo paints the enormous backdrop of China.

Written by Charles Montgomery