Koreans Increasingly Turn to Closed SNS

You might think that with social network services (SNS)—otherwise known as social media—the more open, the better. In Korea, however, “closed” SNS are on the rise, and have been since the end of last year. These closed services differ from traditionally “open” services such as Twitter and Facebook in that they allow only the user and select family and friends to share and view photos and posts. Typically, you register as someone’s friend by invitation only. These services let users enjoy the benefits of deeper, unfettered communication with friends and family while at the same time providing better protection of their private lives. Closed services have proven especially popular recently, with users turned off by what some feel is the excessive openness of existing SNS.

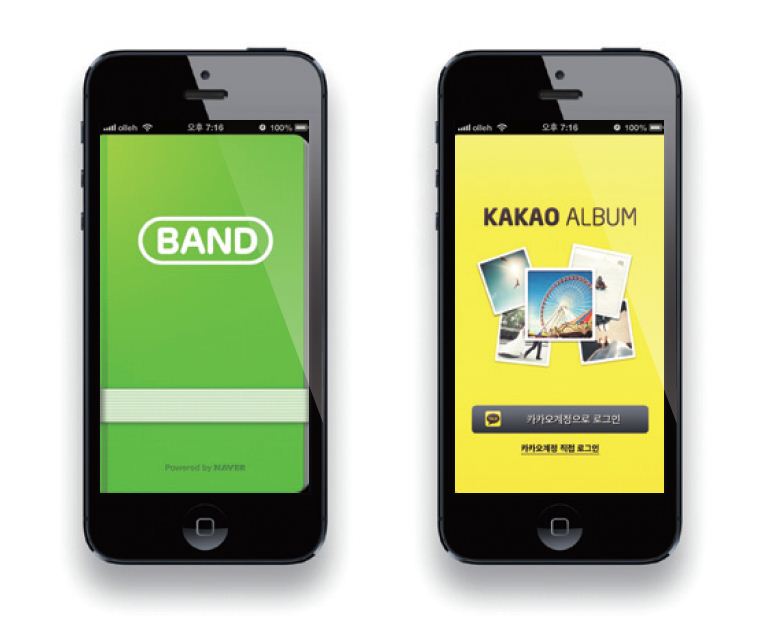

Naver Band and more

One of the more successful closed social networking services is Naver’s Band. Like Twitter, this app allows for instantaneous mobile communication. Where it differs, however, is that it allows users to divide followers into different groups, each one with differing levels of access. Whereas family members may have complete access, mere “friends” may be able to see only a little. The app comes with a bulletin board, photo gallery, chat room, online schedule, and user

management menu. Each user can register up to 5,000 friends. Just 40 days after it opened last year, the app had been downloaded one million times. It now has about six million users.

Band is not Naver’s only contribution to closed SNS. Naver’s Japan office released the messaging app Line in 2011, not long after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. The disaster had exposed the deficiencies of existing communication systems. Just eight months after its launch, it had 20 million users spread throughout several different countries. By June

2012, it had reached 40 million users.

Another popular closed service is Path, an American service launched in 2010. Path specializes in private messaging, keeping discussions “just between us,” as they say. Even more private is the Korean service Between, which describes itself as a “a beautiful space where you can share all your moments only with the one that matters.” Released in Nov

2011, Between recorded 2.2 million downloads within its first year.

Korean app giant Kakao has gotten into the game, too. In February, the company released Kakao Album, which allows users and their friends to create photo albums of their very own. If users would like to promote their albums further, they can share what they post via Twitter and Facebook, too.

Privacy concerns

The rise of closed SNS is related to growing concerns about the privacy protection of existing social network services. There have been numerous cases both in Korea and overseas of cyberstalking and cyberbullying by way of Facebook and Twitter. The resourceful user can mine a good deal of private information from SNS; this data can later be used in the commission of cyber crimes. In 2011, criminals hacked one of Korea’s largest social network services, Cyworld, making off

with the personal data of 35 million users.

To make matters worse, deleting a social network presence can be a difficult and timeconsuming process—and if much of your data was shared with SNS friends, it can be virtually impossible.

Korea’s gregarious Confucian culture can present additional problems to existing SNS users. What do you do when your boss wants to friend you on Facebook? Some workers feel compelled to leave comments on the Facebook posts of their workplace superiors, lest they appear disinterested. One female office worker in her 30s recently told the Dong-A Ilbo

she needed to quit Facebook due to stress—superiors at work constantly left disheartening comments on her posts, she grew tired of kissing up to her superiors by writing comments on their posts, and she was constantly forced to explain her posts to concerned coworkers.

Written by Robert Koehler