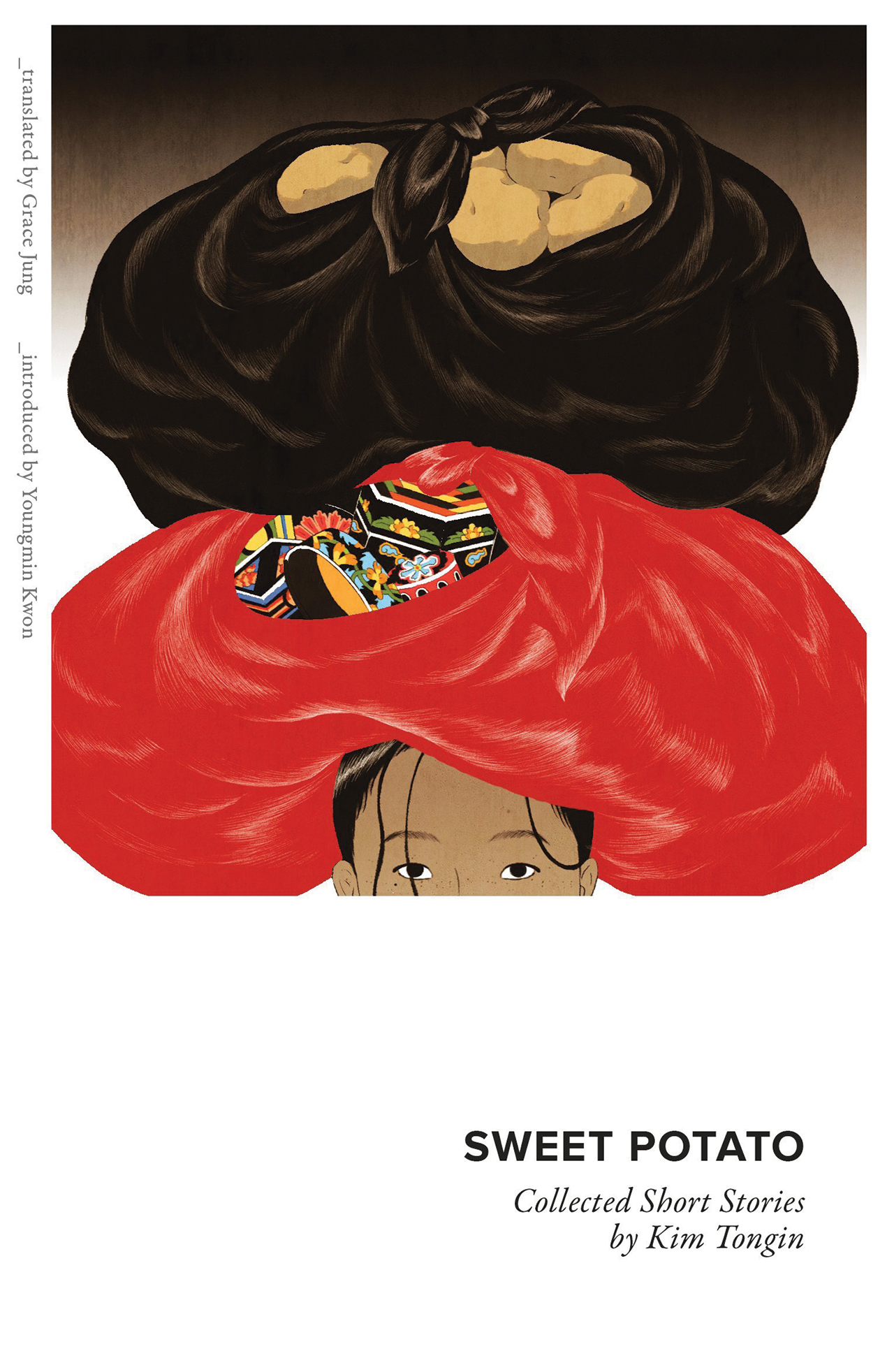

‘Sweet Potato: Collected Short Stories by Kim Tongin’ offers an unfiltered look at life in early modern Korea

‘Sweet Potato: Collected Short Stories by Kim Tongin’ offers an unfiltered look at life in early modern Korea

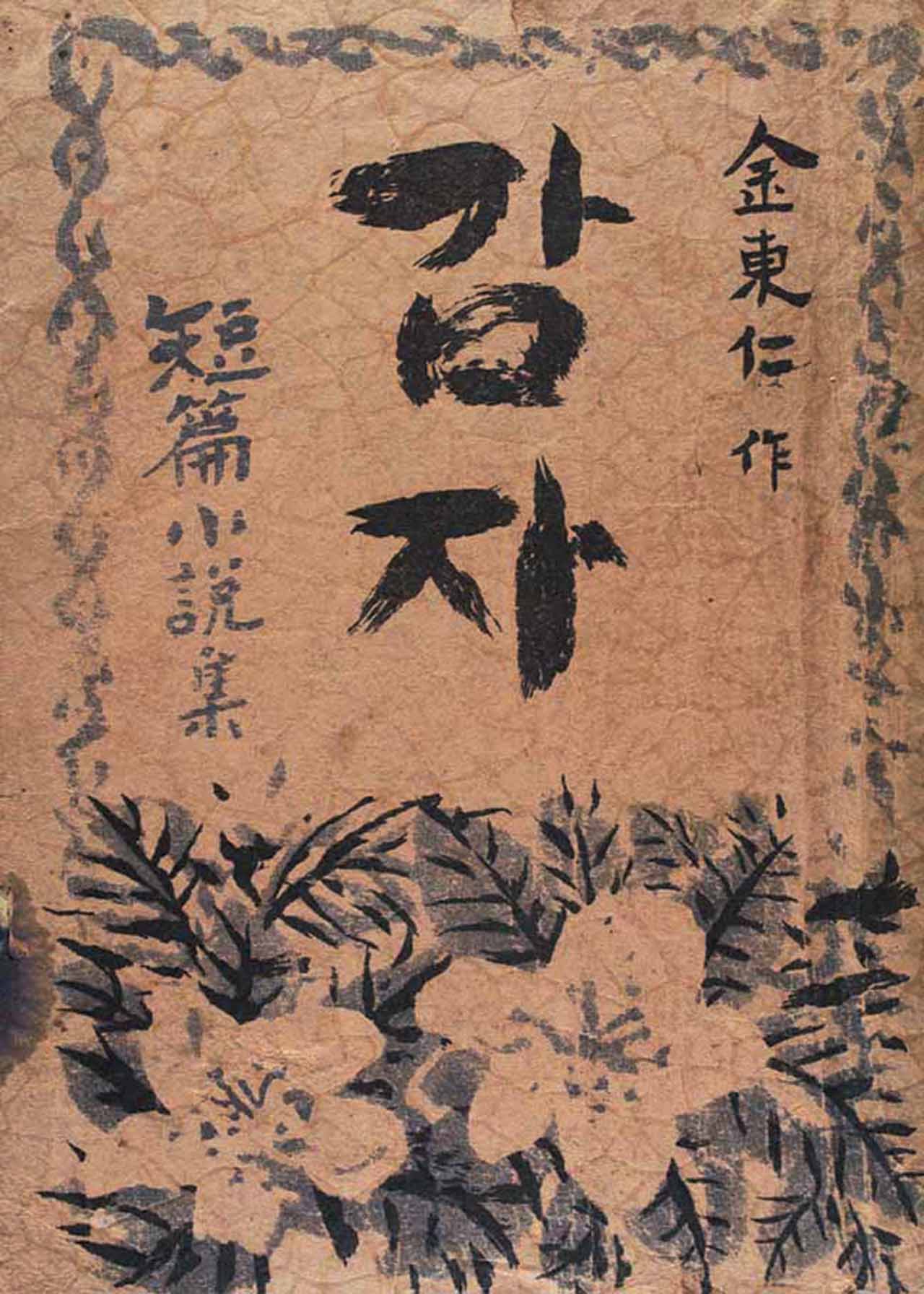

A wave of modern and post-modern Korean fiction, much of it written by women, has been translated since the turn of the century, replacing the male-dominated traditional Korean fiction of the 20th century. Which is why it is of some note that Honford Star Press has just released “Sweet Potato: Collected Short Stories by Kim Tongin.” Kim is not just one of the original, male authors of Korean modern fiction, he is also one of the authors, along with Yi Kwangsu and others, who consciously defined Korean modern fiction. In fact, Kim founded the first literary magazine in Korea, Creation.

The somewhat dueling introductions between critic Kim Youngmin and translator Grace Jung do a good job of placing Kim Tongin as a “naturalist” in Korean fiction; that is to say, one who focused tightly on the traumas of Korean life as opposed to dreams of the future, as found in the work of Yi Kwangsu (“The Soil” or “Heartless”). Readers looking for the easy optimism of the future will not find it in Kim’s work. What they will find is surprisingly modern and well-written works.

Kim’s writing is good. As the introductions note, he was a bit of a trailblazer in narrative style, regularly using the past tense, third person and “story within a story” structures. This is also to say that Grace Jung’s translation is readable and only rarely intrusive.

The centerpiece story is, of course, “Sweet Potato.” “Sweet Potato” begins with one of the best opening lines in Korean fiction, “Fighting, adultery, murder, begging, imprisonment – the slums outside the Ch’ilssŏng Gate were the point of origin for all of life’s tragedies and conflicts.” The story follows young Pongnyo, a principled young woman, after she is sold into marriage to a worthless older man. After a fruitless struggle to survive by her principles, she slowly discards her morality, gaining money and confidence. Her successes are temporary, however, and she ends up killed in a confrontation she has caused.

In the thematically related “Barely Opened His Eyes,” “The Old Taet’angji Lady,” and “Mother Bear,” Kim explores similarly grim life-arcs for women of different backgrounds. “Like Father, Like Son” gives the same treatment to a philandering man.

“Flogging” shares this dark tone. Based on Kim’s own experience, the narrator describes a nearly unbearable existence in a prison cell, and the sounds of a fellow prisoner being beaten outside.

Not all the stories are grim in quite this way, though none are exactly cheery. In “Fire Sonata” and “The Mad Painter,” Kim explores the roots, inspirations and relationships between art and insanity. In “The Traitor,” Kim takes a swipe at authors like Yi Kwangsu, who was a fairly enthusiastic Japanese collaborator. Two other stories worth mention are “The Life in One’s Hands,” an interestingly structured philosophical treatment of the precarity of life, and “Notes on Darkness and Loss,” a story of a mother’s protracted death.

All the stories here are good, and relationships are real and come with comprehensible motivation, not a little thing in Korean literature of this era. With their modern themes, structures and characters, all the stories are a pleasure to read, and the collection is a good introduction to early Korean modern fiction, its concerns, and evolving style.

Written by Charles Montgomery