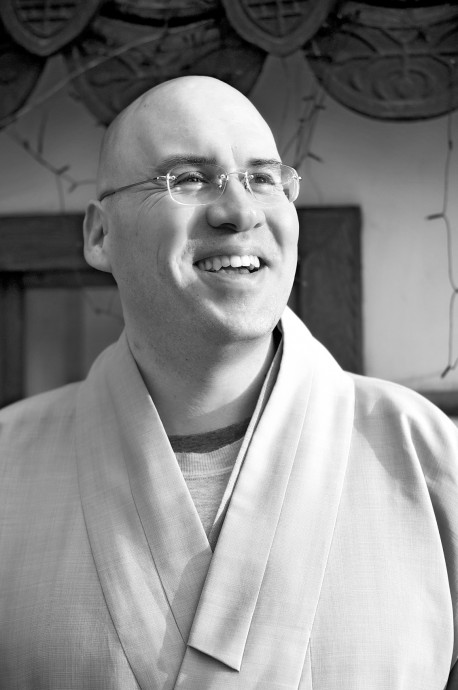

American-born Buddhist monk Chong Go Sunim describes a day in the life at a Korean monastery

[dropcap letter=”W”]hat’s life like as a foreign monk or nun, or sunim, in Korea? Mostly lots of work and culture shock!Okay, perhaps I am being a bit flippant about it, having spent the last 20-plus years as a monk here, but it’s certainly not a life of drinking tea under pine trees that some people seem to expect. But, if it truly calls to you, you’ll get a chance to learn about spiritual practice and meet some wonderful people. There’ll be challenges and hardships you didn’t expect, but also a chance to grow and become a better person.

Learning from words and spatial energy

The day starts early, between 3:15 and 3:45 AM at most temples. It’s no easier to get out of bed for me than for anyone else. There is no secret, other than “go to bed early!” Even then, some mornings I have to visualize myself sitting up and then moving before it will happen. Laying in bed and waiting for my body to move of its own accord doesn’t work very well.

If you live at one of the large meditation halls or sutra study halls, then you may be sleeping in a large, Korean-style room with 10 or more people. It’s easier to get going in the mornings because someone turns on the lights and everyone else is moving around, getting dressed and putting away the traditional Korean bedding. There’s only one downside to sharing the same room: snorers, although if they’re really bad, they usually get exiled to a different room.

Morning service follows soon after, with just enough time to wash your face and get a drink of water. Everyone makes their way to the Dharma Hall and takes their regular seat, usually kneeling. At some larger temples, the service begins with a large bell being struck 33 times. Some temples strike a cloud-shaped bronze plate instead, but many temples skip these and start with the smaller bell inside the Dharma Hall. A large, outdoor bell can be heard clearly for more than a kilometer, so if the temple is in a city, the neighbors may not be so happy with you. Especially at 4 AM!

Sitting there in the quiet, listening to the bell is one of my favorite times, particularly when the electric lights are off and the only light is from the candles in front of the Buddha statue. There’s something very profound there that I can only guess at. Sometimes, I think that the sincere spiritual practice of Buddhists over decades or centuries has left a residue or an echo. It’s as if the Dharma Hall has absorbed that energy and now radiates it back.

The service itself calls all beings together, encouraging them to remember the truth that we all have a great treasure within us. The chanting reminds us that we are all inherently complete and part of the same whole. “Find this! Find this!” it seems to call out.

Remembering this, and learning to live in accordance with it, is the purpose and essence of spiritual practice. Sometimes we learn this from the words of the texts, and sometimes we learn this from the energy of the place.

Work never stops

Morning service usually lasts around 30 minutes. Afterward, some temples will have sitting meditation, others will have sutra chanting and at still others nothing formal is scheduled. Sometimes Korean monks and nuns will do their cleaning or other chores during this time. Those who work in the kitchen will head back there now to help the head cook, who started work at around 3 AM!

The amount of work it takes to maintain a temple beggars belief. There’s always something that needs doing. Rooms, halls and courtyards have to be cleaned once or twice daily, fruit needs to be carried up to the Dharma Hall and then back, there are ceremonies to conduct or attend and an endless number of other tasks to complete. In the midst of this, if you can find some time to learn Korean, so much the better.

Breakfast is at 6 AM in nearly all temples. It can be very formal and traditional, using the four bowls called baru. Or it may be simply cafeteria style, with aluminum food trays that look like military surplus.

Dietary adjustments

Food is one of the harder things about being a monk or nun in Korea. You may think you like Korean food, but wait until you’ve eaten it three times a day for a year! Most foreign monks and nuns find that they need to have something familiar at least once or twice a day.

If there are only foreigners at a temple, this is fairly easy to do. If you’re at a Korean temple that has only Korean food, however, it’s usually necessary to eat lightly with the other monks and then eat something more familiar afterwards, such as oatmeal or peanut butter-and-jelly sandwiches.

Some Koreans won’t understand this and will suggest that more kimchi or dwaenjang soup will help! But those who’ve been overseas will understand immediately. One monk who was very familiar with traditional Korean medicine explained it to me like this. “Your body was built with the energy of certain kinds of food, so trying to switch foods too suddenly can’t help but cause problems.”

Tea time

After breakfast is the time usually set aside for cleaning. Afterward, monks will sit together on the floor of somebody’s room to drink tea. You may see monks carefully preparing Korean green tea, steeping it and then pouring it, with a small cup for everyone. Or they may be making the dark and earthy Chinese Pu’er tea, which is often more popular in the winter.

These days, it’s not at all uncommon to find the monks making coffee instead. Rather than steeping tea leaves, they’ll be hand grinding the beans and then making a “pour-over,” finally dividing the concentrate among a semi-circle of cups to make an “americano” for everyone there. I rather like this new tradition!

At noon and in the evening there will be more ceremonies. Some temples may have formal meditation periods, and at all temples there will be work to do throughout the day, guests to meet and people to counsel.

So this is a small taste of what life is like for a Buddhist monk or nun here in Korea. I hope you have a chance to experience a bit of this for yourself while you’re here.

Less blame, more positivity

Sometimes I’m asked what advice I can give those who don’t live in a temple or who aren’t interested in Buddhism. There are two things that anyone can work on, and that have the power to completely change your life.

First, don’t blame or resent others.

Second, always view things positively.

Resentment, blame and hate cut us off from others, and like fractals, they can go on without end. The thoughts we give rise to create the world around us and nudge it in the direction of our choosing.

Experiment with these and see for yourself how your heart feels afterward. If you work at it, you may notice joy and laughter coming back into your life!

[separator type=”thin”]More info

American-born Chong Go Sunim was ordained as a Buddhist monk in Korea in 1993. He resides at Hanmaeum Seon Center in Anyang, where his duties include translating Buddhism-related texts into English.

Written by Chong Go Sunim