Director Jang Kun-jae spins together two stories into a single, sweet film

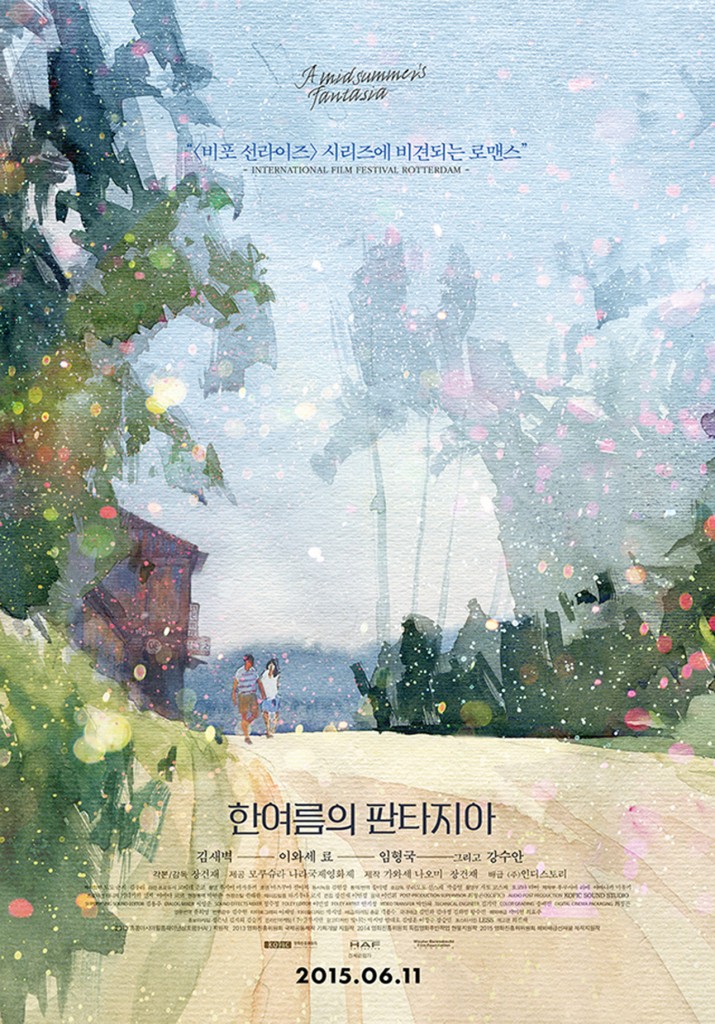

Korean film has a well-deserved reputation for quirky, interesting films for both the mainstream and independent cinemas. While perhaps better known for its boisterous and innovative (read: violent) mainstream films, there’s a large and innovative independent film scene that often takes a quieter, more reflective approach. Director Jang Kun-jae’s third film and most recent film, “A Midsummer’s Fantasia (한여름의 판타지아)” brings its own special understated charm to the summer film scene.

Bringing two stories together into one cohesive whole

The film is divided into two parts, with each sharing both a setting and actors. In “First Love, Yoshiko” a Korean director and his assistant/translator are in the sleepy Japanese town of Gojo, just outside Nara, to scout locations and stories for an upcoming film. Shot in black and white, the first part of the film uses a sparse cast and interviews with real locals.

The second part of the film, “The Sakura Well” uses color and a more traditional narrative approach to tell the love story of a Korean actress briefly escaping disappointments at home who encounters a local persimmon farmer. Using a tiny cast in multiple roles and a few non-actors, the film builds a strong sense of sympathy for both the location and the travelers visiting it, however briefly. As the story continues, the two parts start to overlap in ways both expected and surprising, weaving the narratives together.

Getting the measure of Gojo City

“This film is about a Korean director who goes to the Korean countryside. In part one, the director explores and hears the stories that appear in part two. Those two stories each influence each other,” explains Jang Kun-jae. Youthful and reserved – a common trait among his other works – he made the film at the request of renowned Japanese director and producer Kawasae Naomi specifically for the Nara International Film Festival, where it premiered last fall before touring other international film festivals, including a premier in a Korean theater this past July. “It was a condition of making the film that it be made in Gojo. The experiences of the director therefore reflect my own experiences of going to the town. I couldn’t choose the place.”

Slowing down film to the pace of life

For viewers used to the more fast-paced nature of mainstream cinema, the film’s trajectory can seem slow, but Jang disagrees. “I don’t really see it as a slow film. It’s at the pace of my life. It’s not Mad Max or a commercial film.” Indeed, despite the slower progression, the film never drags, and the more thoughtful exploration of the characters and their stories helps give it not just its charm but also a sense of realism that many films lack. The work has been compared to Richard Linklater’s “Before” series for the gentle and semi-improvisational way in which it unfolds, particularly in the second half.

The difference in tone between the more statically filmed, black and white documentary-style of the first and the warm, meandering tone of the second is important to Jang, who used the split to do more than just tell interlocking stories but also express his feelings. “I chose black and white for the first part because it all seemed a bit colorless to me.” The town itself is one of many in Japan that is watching its population age and shrink as younger people leave for the cities.

Putting the audience in the director’s place

Another important aspect of the film was how it sought to reflect the realities of travel and the challenges of communication. In the first half, Jang uses subtitles sparingly, making the audience wait along with the characters as the director’s assistant renders Japanese into Korean. He explains, “If I’d put in subtitles for everything, the audience would get all the information twice. This puts them more in the director’s place. When you’re traveling, you just have to wait for the translation.” In the second half, the dialog is in Japanese but reflects the simplicity that comes along with communicating in a second language as the actress and persimmon farmer leisurely meander between the small town sites.

“Part one is my story. Just like the director in the film, I went and interviewed people and came back to Japan. For part two though, I didn’t really have an idea. It was mostly improvisational,” says Jang. “Normally I prepare a lot for each film, but this time I worked with Kawase and asked myself ‘How would Kawase film this?’ and talked a lot with the actors to come up with an approach, kind of like jazz music. I didn’t really know how it was going to turn out. I didn’t have a script.”

‘I didn’t really know how it was going to turn out. I didn’t have a script’

The improvisational jazz of movie making

“Kawase called me to say ‘Let’s make a movie,’ and I thought it would be a great experience. It’s something I really wanted to do.” Perhaps more than any other influence, Kawase and her documentary-influenced style is evident in the feel of the film, as well as changing how the movie itself was created.

Jang made the changes from his normal approach to film when working with Kawase, recalling, “When I shot this, I had only a partial script, but my co-producer Kawase Naomi called me to tell me to hurry up. I went to Gojo City and finished part one, and the actors and I had a few days to rest. I went to my staff and asked for three days to write a script for part two. But I had no idea! For three days I only worked and talked with my actor and actress about their characters. On the last day, we fixed our ideas for the plot and said ‘You will be an actress and you will be a persimmon farmer.’”

We went day by day with no idea

“I shot the first day and we went day by day with no idea. Just ‘Hey, your character came here to refresh so she can work well as an actress, but she failed an audition.’ And we shoot here and there, using information we’d gathered from the first part, all in sequence … The next morning, as they walked, we would check the blocking. As we worked on that, we would use the dialog they came up with. And they would connect it back with what we’d done for the first part.”

“This isn’t how we usually do it, “ Jang notes. “Normally you have to get money, do the casting, scout the locations, and prepare a lot of detailed information. That’s my usual style. But I couldn’t do it this time – there wasn’t time … The process was really improvisational. The film took two years to complete, but we finished all the filming in only three weeks: five days for part one, six days for part two.”

Moving ahead to new challenges

The challenging nature of making the film has paid back dividends, though, in moving Jang in new direction and expanding his style. However, his fans will have to wait to see what happens next. Jang has his own plans: “I’m going to rest. I’ve been working on films for a few years, totally throwing myself into it, and now it’s time to rest and spend time with my family for the next two years, at least. I’m just going to rest with my family.”

Written by Jennifer Flinn

Photographed by Ryu Seunghoo