Institute for the Translation of Korean Classics Director Lee Myung-hak strives to make Korea’s classical canon both accessible and relevant

“No matter how scientifically developed future society is, how much cutting-edge knowledge it has or how materially rich it is, if it lacks an understanding of humanity or lacks spiritual wealth, it’s all meaningless. It is in the classics that we find the answers to what it means to live as a human being, what a person’s duty is, what it means to sacrifice yourself and show consideration for others.”

Institute for the Translation of Korean Classics Director Lee Myung-hak is a man who has dedicated his life to not only preserving Korea’s classical literature heritage but also to making that heritage, much of which having been written in classical Chinese and intelligible only to the most educated specialists, more accessible to the public at large. It’s a weighty and very time-consuming task, but it’s also one that the longtime professor of classical Chinese education at the prestigious Sungkyunkwan University has taken to heart. “The classics give us time to reflect on the meaning of mankind’s existence. In so doing, we get to look back on ourselves and our current lives,” he says.

‘No matter how good a classic may be, if nobody reads it, it’s useless.’

An old road to tomorrow

Located in the appropriately tranquil district of Gugi-dong on the slopes of Mt. Bugaksan, the Institute for the Translation of Korean Classics got its start in 1965, when several dozen leading scholars came together to form the National Culture Promotion Association. The original collective was private, but in 2007, it became a national organization under the administration of the Ministry of Education. Its major duty, as its current name suggests, is the collection, sorting and translation of classic documents, including personal writings, historical documents and other writings from Korea’s pre-modern eras.

Lee explains that the classics are often called an “old road heading to tomorrow.” It’s an odd phrase, yet an appropriate one when one considers the role of classical literature. “Through reading the old classics, we can find the path by which we shall live tomorrow,” he says. “Making and finding that path is our job, but the classics establish the direction.”

The importance of classical literature in pointing the way forward has not diminished over time. In fact, it may be more important than ever, given the complexities of modern-day life. “The classics have a rare power to make us fundamentally reflect on whether the way we are living now is right, whether we are really living like human beings,” says Lee. “Stuck in competition and hardscrabble lives, we are caught up in living day by day. We have no spiritual energy to spare, either. In such times, reading the classics can be an opportunity to look back on our lives.”

Reading the classics can be a life-changing experience: Lee recalls one homeless man who got his life back on track after listening to a humanities lecture. Provided with an opportunity to reflect on his current state of affairs, the man decided he needed to make some changes. “To look back on how you are now while reading the classics is the same as looking at yourself in a mirror. That’s the power of the classics,” says Lee.

Opening the classics to the masses

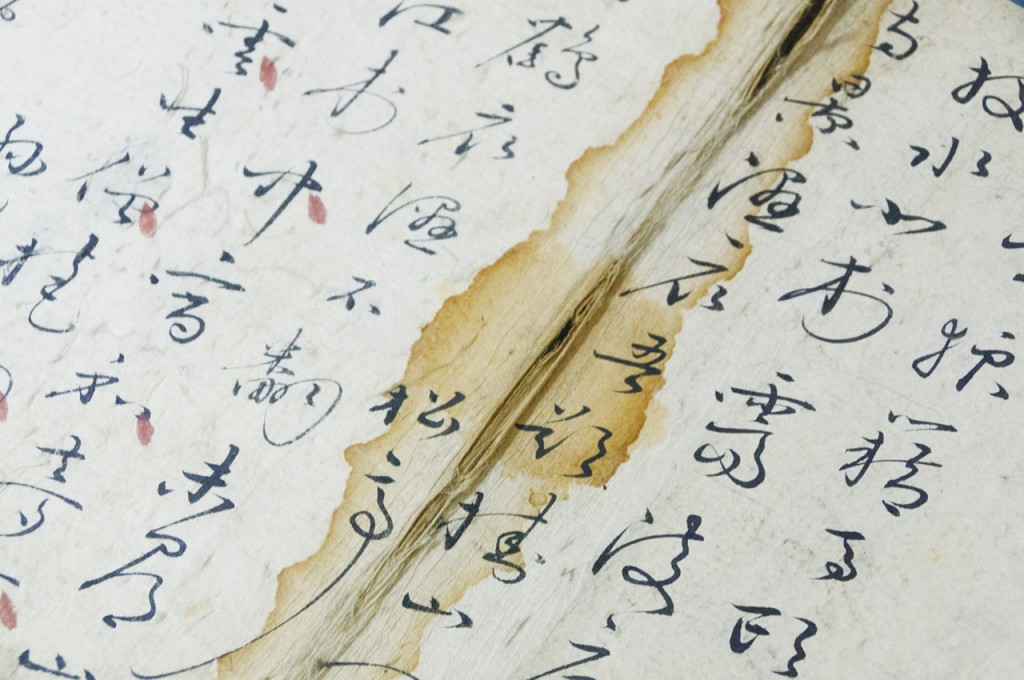

Just as much of the classical canon of the West is written in Latin and ancient Greek, much of Korea’s classical literature is written in classical Chinese, a language that cannot be understood by the vast majority of the general public. Proper translations, therefore, are critical if this vast corpus of knowledge and wisdom is to be passed down to the next generation. Properly translating classical texts is a massive undertaking, however, especially if one’s aim is to make the resulting translations both intelligible and enjoyable. The lack of readable translations has put many people off from reading the classics, in fact. “We must produce books by making anthologies arranged so that they are easily accessible to the general public and have simple explanations and well-written sentences,” says Lee. “No matter how good a classic may be, if nobody reads it, it’s useless.”

In particular, Lee feels it is important to make the classics comprehensible to the most impressionable of minds – those of the children. “I think it’s important that we make it so that children can easily learn what it is to live properly through the classics,” he says. “Because children are young, the good books and the feelings they get through those books can become not just one person’s personality but a valuable asset they won’t forget for a long time.”

The success of the ongoing KBS historical drama “The Jingbirok: A Memoir of Imjin War” (2015), based on the memoir of 16th-century statesman Ryu Seong-ryong, Korea’s prime minister during the chaos and destruction of the Japanese invasions of 1592-1598, has sparked something of a renewed interest in classical literature. Lee cautions that, as is so often the case, screenplays can sometimes play loose with historical facts in order to tell interesting stories. “That said, I think the fact that ‘Jingbirok’ has gotten rave reviews from so many viewers is not solely due to it being exciting,” he says. “It is because we can see how the behavior of the leading classes as they respond to national crisis through the Imjin War, which left a lasting scar on our people. That is to say, as we look at the past, we see our current reality.”

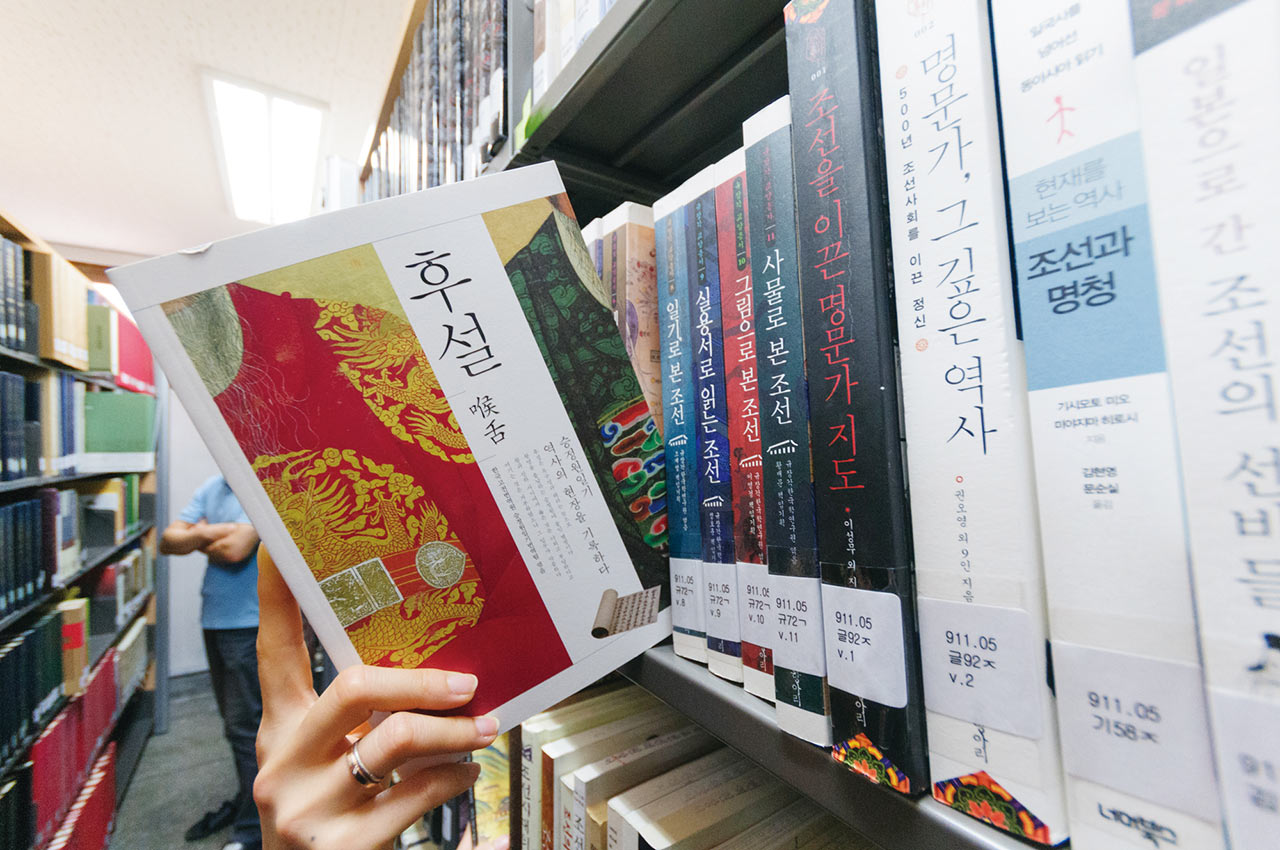

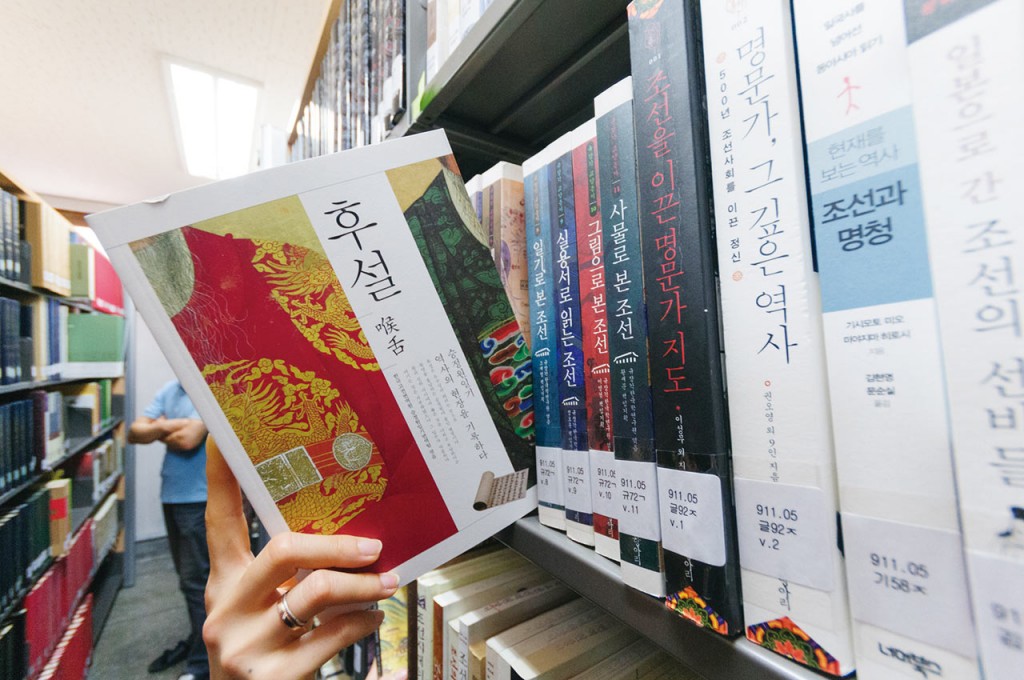

Book on history of the Joseon Dynasty’s royal secretariat, based on the institute’s 20 years of research

Need to know your subject

To get a handle on the scale of the Institute’s translation projects, consider this: The first translation of the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, the official archive of the royal dynasty that ruled Korea from 1392 to 1910, took over two decades, lasting from 1971 to 1993. Due to the final edition’s prevalence of anachronisms and mistranslations, the institute has since begun retranslating it. At present, one of its major projects – the translation of the Seungjeongwon Ilgi, the daily record of the Joseon Dynasty’s royal secretariat – is scheduled to take 48 years. That original Chinese version of this text is 240 million characters in length, several times longer than all the official histories of old China. “We could probably lessen the amount of time needed to translate the work if we had the budget support, but we don’t,” says Lee.

Many people believe that all that is needed to translate classical texts is an understanding of Chinese characters. But as any translator will tell you, knowing the original and target languages is only part of the project. “If you translate Chinese character sentences by the letter, you could mistakenly convey the meaning,” says Lee. “You can translate accurately and convey the proper meaning to readers only if you know the social, political, economic and cultural background of the times. That is very important.”

Lee also notes that you need to know who your target readers are, since translating for the public at large is a very different task than translating for academia; a clear divide must be established between accessible, easy-to-read translations for the public and intensive translations for the academy, he says.

One classic he recommends for the general public is the biography section of Samguk Sagi, a 12th-century text detailing the history of Korea’s Three Kingdoms Era (57 BC-AD 668). The translation is easy to read, he says, and includes information on the lives of the countless historical personages who lived during one of Korea’s most dramatic epochs. Through their lives, Lee says, we can learn a lot: “If you read the records of these people and compare their lives with yours, your own life will be enriched. It’s important to have a questioning and sympathetic attitude as you read, asking yourself how the people of old could have lived as they did, what their lifestyles were and what was the significance of their lives. I think it is important to develop an affinity with the classics in this way.”

[separator type=”thin”]More info

Institute for theTranslation of Korean Classics

T. 02-394-8802

1 Bibong-gil, Jongno-gu, Seoul

Written and photographed by Robert Koehler