[box_light]Native Children

A discussion on the Korean-American experience in Korea [/box_light]

Written by Felix Im

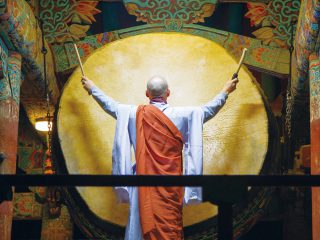

Photographed by Ryu Seunghoo

Gyopo: Naver’s Korean-to-English dictionary defines the word as an “overseas Korean” or a “Korean living abroad.” The word’s actual usage in both written and spoken Korean implies that it includes all of the following: native-born Koreans who emigrated as adults; native-born Koreans who emigrated as infants, children or teenagers; foreign-born Koreans who were raised abroad under native-born parents; and, depending on who you talk to, Korean adoptees who were raised under non-Korean parents. Some gyopos speak perfect Korean; some speak none at all: Most seem to fall somewhere in between. Some identify themselves with Korea to a great extent, while others seem completely indifferent. In short, gyopo is a complex word with endless connotations and no single definition – but then again, most words concerning ethnic identity or nationality are often just as confusing as the individuals they describe.

Whatever the word means, most people who are categorized as gyopo will probably agree that their experience of living in Korea is markedly different from that of both full-on natives and non-Korean expats. To investigate this experience further, SEOUL gathered four panelists and asked them to share their views on what it means to be a gyopo in Korea. Teri Ham, a former IBM employee turned creative content director, was born in Texas and grew up in various places around the United States. Amy Mihyang Ginther, a voice and acting coach, is a Korean-American adoptee who was born in Gyeongsangbuk-do but grew up in upstate New York. Peter Kim, an assistant professor at Kookmin University, is NYC-born but Jersey-raised. Sandy Cho, a Yonsei grad student, was born and raised in Korea but was mostly educated in the States. The writer himself was born and raised in Colorado. Such a mix of very different types of Korean-Americans made for a lively and stimulating discussion on what the Korean identity means.

To start off, how “Korean” did you perceive yourself before first coming or coming back here? How much did you identify with Korea?

Teri — Not at all. I spent a good amount of my childhood in Colorado, where it was Caucasian-dominated, so I didn’t have that sense of Korean community, and I think most of my white friends just considered me the same as them.

Amy — I was fortunate enough to have a Korean adoptee community growing up, and I identified myself as not necessarily Korean but definitely Asian – and different. I’d always felt different.

Peter — To me, it was more half-and-half. I grew up in a large Korean community in Jersey, so I always had that community, but I always knew I wasn’t completely native.

How Korean do you feel now, after all your time here?

Amy — Actually, when I first came here, I felt very non-Korean. I initially arrived with my dad to visit my biological family, and then came back alone to live with them for a month, and that experience made me feel very Western and American. I felt like a closet Westerner the entire time. Now, I feel as Korean as I want to be, with no pressure to swing one way or the other.

Sandy — When I first moved to the States, I considered myself 1.5 generation, but now that I’m back here, I just consider myself a Korean who speaks English. I have citizenship here, and I know my rights here, whereas back in the States I was always a foreigner and paperwork was always complicated.

Teri — I don’t know how to answer that question. Everything’s so global these days; it’s hard to categorize your identity that way. I am what I am, and I’m comfortable with it.

Do you sometimes feel that Koreans treat you differently than they treat non-Korean expats or other native Koreans?

Teri — I was very lucky, because I got the best of that experience. I was welcomed very warmly, and people respected my independence. I’ve heard of other people being treated very poorly, but for me that wasn’t the case.

Peter — Only when I say something in imperfect Korean and a non-Korean foreigner says the same thing in the same way but gets much more slack. They expect more from me because I look Korean, even though I’m still a foreigner in many ways.

Amy — There seems to be that cognitive dissonance that prevents people from understanding why I wouldn’t speak perfect Korean. Also, there’s a very confused feeling here towards adoptees, a sense of shame mixed with jealousy at those who were able to go.

Sandy — For me, my friends who just grew up here always treat me like I don’t know anything about Korea, and when they find out that I do know certain things, they act very surprised. It’s very condescending. I mean, I’ve even been asked if I can eat tteokbokki. Come on! Also, whenever I say something they don’t agree with, they just say, “You’re being American; you can’t think that way in Korea.” I’ve learned not to argue.

Have you ever felt pressured to be more “Korean” than you actually are?

Peter — When I’m driving, everybody always tells me to just cut everyone off and be more aggressive. I don’t drive that way; I’m not willing to risk hurting someone.

Amy — I’ve learned to not eat when I’m not hungry, or to not take drinks I don’t want – but I’ve also learned to just surrender when people want to take care of you. At first, my Western, more independent side rejected any interference. I don’t feel comfortable with being pushed to get married, however.

Teri — No, I’ve always been very clear when I consider something unacceptable. But when I was asked about when I planned to get married and have kids during my interview, I wasn’t offended. I knew I was in different territory.

Sandy — Speaking of gender expectations, I’ve just become numb to it – just accept it for what it is. Also, you just can’t chill here. You always have to be doing something.

The discussion swerved into gender equality, social stigmas and oppressive drinking culture. After some emotional accounts and heated discussion, we all agreed that the Korean identity can be just as flexible as that of America, and that it doesn’t have to be correlated to restriction or unhappiness. Being proud of being Korean means being able to transform Korea’s cultural image into what you want it to be. In the end, although it has its drawbacks, being a gyopo helps one to appreciate the benefits of a cross-cultural background.