2017 Venice Biennale artist Lee Wan offers a critical voice from the Korean art scene

Lee Wan is taking the art world by a storm.

After winning Leeum Samsung Museum of Art’s first Artspectrum Award and participating in the 10th Gwangju Biennale in 2014, he continues to awe the public with his unpredictable multi-media work ranging from installations and videos to sculpture. He explores the effects of the capitalist system in the contemporary world, particularly in Korea. He also questions the system at large and offers various perspectives to challenge the norm. Through his work, he suggests a way to escape from the system.

“Much of my work stems from fundamental questions like ‘Why am I me?’ and ‘Why did I choose this?’” he says. “When I make a choice, it is not without the influence of the society. This perception affects my personality, what I’ll do in the future, and the decisions I make. I explore this psychology in my work.”

Entering the international art world

Lee just returned from the 57th Venice Biennale, where he was selected to represent the Korean Pavilion, a pavilion that earned a good deal of international attention and praise. Running through November 26, the pavilion’s exhibition, “Counterbalance: The Stone and the Mountain,” examines the relationship between individual stories and national histories, spotlighting Lee’s and artist Cody Choi’s work under the direction of curator Lee Dae-hyung. Both artists portrayed “counterbalance” through the puzzling, even destructive, lens of globalization in the contemporary world, especially Korea. “The response was explosive,” said Lee. “Curators and artists worldwide praised the Korean Pavilion. Many people who gave us feedback said we’d touched upon a subject that many other pavilions had closed their eyes to.”

Three of Lee’s works are on display at the Venice Biennale: “Mr. K and the Collection of Korean History,” which symbolizes Korea; “Made In,” which represents Asia; and “Proper Time,” which reflects the world.

The installation “Mr. K and the Collection of Korean History” is a collection of 1,412 photographs and personal objects that belonged to the late journalist Kim Ki-moon. Lee, himself a keen collector of artifacts and antiques, discovered the collection, which he purchased for just USD 50, at an antique market in Seoul’s Hwanghak-dong district. Kim’s life mirrored Korea’s dramatic modern history – he lived through the Japanese occupation period, the Korean War, the post-war economic boom, military dictatorship and the transition to democracy. Lee explains, “Kim’s life shows how personal history flows into the history of a whole nation.”

In the film series “Made In,” Lee deconstructs the effects of the colonialism that inevitably infiltrates the neoliberal economies of Asian nations. Examining what goes into preparing a breakfast, Lee traveled to 12 nations to take part in the creation of the ingredients, utensils and clothing. He visited rice fields in Cambodia, silk manufacturers in Thailand and sugar farms in Taiwan to participate in and document the primary stages of production. “In Cambodia, I saw young people on smart phones walking around with bare feet,” he recalls. “They don’t have a TV, but they know how to use Google. Young girls walk around with pasty white faces to resemble actresses on Korean soaps. Pasty faces with bare feet and smart phones are replacing beautiful, long-held traditions.”

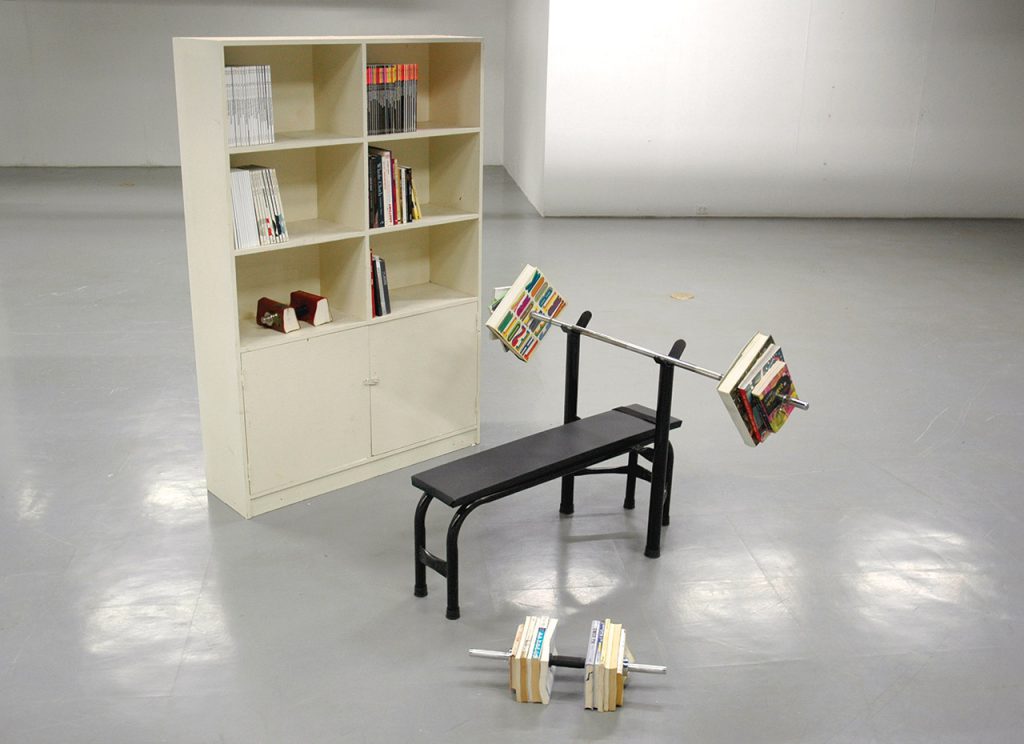

Book Sporting Goods, miscellaneous materials, 2006, © Lee Wan

Sacrifices made for progress

Through his work, Lee highlights the loss of cultural heritage for the sake of modernization. In “Proper Time,” 686 clocks hang on white walls, ticking time at different speeds, the hands moving at paces adjusted to how long different individuals must work to afford a meal. Below each clock is the name, date of birth, nationality and occupation of the individual each clock represents.

The work, while encompassing international perspectives and lives, returns home. In the center of the white room is a sculpture of a family, faces carved out. Lee was inspired by the propaganda posters he saw while growing up in Korea in the 1980s.

He recalls, “Many Asian nations that transitioned from dictatorship to democracy spread propaganda messages like ‘Work hard for a bright future!’ Images of families often accompanied such messages.”

Through the carved out faces, Lee asks if Koreans have truly arrived at the future for which they desperately worked. Though the nation has achieved economic prosperity, it also sacrificed important values along the way. He asks, “The future they spoke of is now. But are we living a fulfillment of the future we hoped for?”

What did Korea sacrifice for the sake of modernization and progress? “Korea is a leaking pot. We need to pour in more water than the pot can hold to survive.We work more to make up for the lack.”

The excessive focus on labor may have elevated Korea to First World status, but it also resulted in cultural loss. “We resemble the understanding of Third World countries when it comes to art and culture,” says Lee. “It’s a sad thing to be so caught up in the busyness of life that we don’t have time to even watch movies. Our only access to culture is through TV and smart phones. This is what Korea lacks and the government must invest in.”

If Given a Chance, I Do Refuse It, object & video, 2013, © Lee Wan

Projecting solutions homeward

After a successful debut to the international art scene, Lee didn’t just sit back. He rolled up his sleeves to create a special gathering of artists and public in Korea. Using the energy and inspiration he gained in Venice, he set off to encourage young artists.

Along with leading artist Choi Dusu, he assisted with planning Union Art Fair 2017, an arts festival and market held in Seoul from June 23 to July 2. Over 200 artists participated in the fair, as did over 8,000 attendees, including couples, families and international guests. Sponsored by the Korea Arts Management Service, it was a one-of-a-kind opportunity for the public to engage with artists and for young artists to share space with more renowned artists. Lee says this was more than an event; it was an rare collaborative effort by the artist community, government, corporations and the public.

Lee is optimistic about the future of Korea’s art scene, an art scene in which artists are being treated more equally with one another. “Over time, authoritarianism seeped in to the art world in Korea,” he says. “People with greater fame wanted better treatment. Things will change now.”

He hopes to take part in more festivals where Korean artists gather and, with luck, capture the attention of international collectors and critics. “I look at Korea optimistically,” he says. “The reason my thoughts sound cynical is because I’m telling you the truth. I’m speaking about hope. When people tell me I’m cynical, I tell them I’m telling it like it is. Things can become beautiful within that, and I envision that kind of hope.”

[separator type=”thin”]More Info

Written by Diana Park

Photographed by Robert Koehler