The future of Korean indie music has never appeared so bright. Or cloudy.

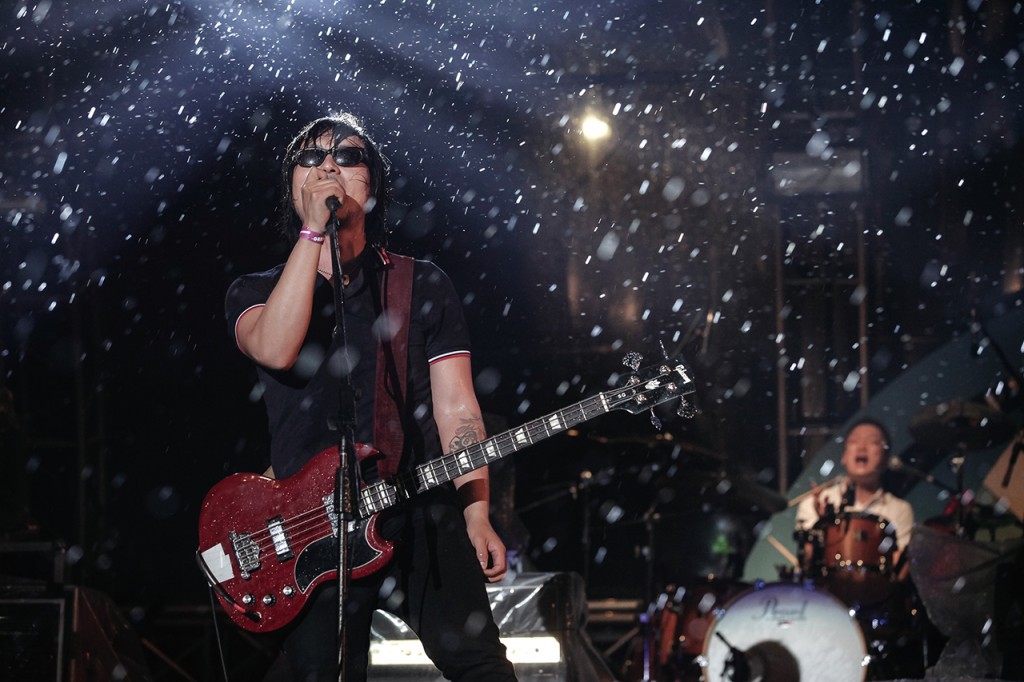

For this year’s Liberation Day, the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II and liberation from Japan, hundreds of thousands of Korean citizens and residents assembled in downtown Seoul. The crowds chanted “Hey! Ho! Let’s go!” along with No Brain, one of Korea’s oldest punk bands. This is a big change when you consider that only about five years ago, the country was saturated with Ramones T-shirts, yet nobody knew who the Ramones were or what shouting “Hey! Ho! Let’s Go!” could feel like.

For most of this century, Korean independent and rock music has been largely neglected, labeled as amateurish, floccinaucinihilipilificated, while the government pumps millions of tax dollars into the K-pop industry.

It’s been a hard sell to the Korean public to accept “amateur” musicians who write their own songs and sing their hearts out when there are also so many polished, chiseled Korean idol collectives out there toeing the government line.

Korean indie, underground, and rock bands, in comparison, are dangerous, not just for the content of their music, but for their alternative lifestyles and inherent resistance to the status quo. This country has a history of conflict between artists and the establishment, with arrests and blacklistings in the mid-’70s creating a 20-year blind spot in Korean rock music history. The musicians that have made Hongdae into a live music destination are not too far removed from their Fourth-Republic forefathers.

Fortunately these bands are taken more seriously these days. Certainly, Korean society has changed a lot even since the ’90s when the pioneering alternative rock group Pippi Band was blacklisted from TV after one member spat at a camera during a recorded performance and flipped the middle finger to a nation of personally offended viewers. Today, Korean bands are kicking ass on TV, and numerous audition reality TV shows are set up to channel these bands to a mass audience and let the nation choose what they like. At the same time, most musicians still work menial day jobs, and their earnings are funneled into supporting their musical activities, tattoos, alcohol, or supporting each other, dreaming of the day their big break comes.

“Music is not business,” said Galaxy Express bassist Lee Juhyun. “Being a musician is no job, and music is playing.” Now the bandmates are professional musicians, but when they started off, Juhyun was a stock boy in a department store, and lead singer Park Jonghyun delivered lunches in Euljiro.

Freedom of expression

These are people who crib their musical styles from wholly foreign genres, but this gives them free range of expression to bare their souls in their own language – or mixed with English if they prefer. Or they get an English-speaking singer, because the music scene is internationalized, with little care about ethnic differences or national origins. In contrast to K-pop, this music scene largely spurns the term “K-indie,” which sets up a nationalistic exceptionalism and implies a close relationship with mainstream music, rather than likeminded musical misfits the world over.

This community has survived thanks to the pragmatic financial interests of musicians not wanting to spend big and risk it all, or thanks to support from mom and dad, and the live music scene is grateful for every KRW 10 coin it can get. Over the past 15 years since live music was legalized, the number of musicians, bands, and venues has ballooned. They’ve grown much faster than audiences, meaning that venues close down all the time, musicians get frustrated and “grow up,” and a lot of fantastic bands hone their craft playing to empty rooms.

Through the late 2000s, the music scene was ageing, without enough young blood coming in, and those who stuck around witnessed each other marrying, having kids, divorcing, going bald, and gaining weight. “Look around the show on Saturday night, there’s no one under 23,” sings Jeff Moses, American lead singer of melodic punk band …Whatever That Means in their song “Our Scene” written in 2011. “Take another look and start to realize, that everyone’s as old as me. Asking all around, ‛Why aren’t there any kids?’ And no one really seems to know. Probably just sitting at home living off the junk on the radio.”

Fortunately, that trend seems to be changing, with youths revitalizing the scene. University-aged supporters are a given, but the kids are getting younger. Most recently, a punk band named Dead Chunks appeared, formed by high-school kids said to all be 15.

The gears are turning, and big things are on the way. But that notion has always been deeply held by anyone who has felt the power of spontaneous live music, and it’s gone nowhere.

Gangnam ironies

Ironically, the singular big breakthrough happened in 2012, when Psy’s “Gangnam Style” went viral and introduced the world to a new conception of South Korea as a hypermodern, materialistic society. Psy himself, not considered part of the K-pop inner circle, opened eyes and showed the establishment that the solutions for popularizing Korean music might exist outside this narrow, tightly controlled market. Suddenly, opportunities to tour overseas opened up for Korean bands, as corporate sponsorship appeared and agencies like KOCCA and DFSB showed their willingness to back talented acts.

It’s both a blessing and a curse that Korea’s live music community is tethered by geography to Korea and K-pop. Korean musicians have an uphill battle to prove themselves to a disinterested and sometimes hostile world. It has historically been especially difficult in Korea to say “Hey, we’re a band, so come listen to our music.”

On the other hand, the tide turned once “Gangnam Style” started racking up the YouTube views by the billion. Government agencies and record companies, aggravated at first that none of their golden geese were the first to break through, eventually embraced Psy’s success and admitted that the next great Korean act might not come from the micro-managed culture industry they’d been cultivating to middling success. Suddenly, it was widely understood that making great music was within reach of the common people, and Korea wasn’t just a country of identical airbrushed drones dancing in unison.

But many watchers of the Korean music scene worry about this. Success brings agents and handlers and endorsement deals which can be toxic to independent musicians. What’s more, the neighborhood around Hongik University, once an accelerator of great bands, is facing gentrification as rent rises and genuine countercultural establishments are replaced with shoe stores.

There has never been a better time to feel pessimistic about the Korean live music community. Nor has there been a better time to feel justified in optimism.

[separator type=”thin”]Info

ten Seoul venues

Club FF good place to go for a wide selection

Jogwang Studio

Jarip HQ the most happening place in Chungmuro after dark

Skunk Hell groundbreaking punk club in a new location in Mullae-dong, now catering to all sounds

Rolling Hall one of Korea’s oldest venues, celebrating its 20th birthday this year

Ruailrock dingy basement in Hapjeong, but aren’t they all?

Evans originators of Monday Project, working toward having live music in Hongdae seven days a week

Club Ta cozy basement venue run by Jeon Sangkyu of YNot? and Beatles cover band Tatles

Freebird2 giant cavernous basement with uncharacteristically great atmosphere

Prism Live Hall one of the larger clubs, perfect for great shows

Badabie rumoured to be closing soon, but one of the nicest live music venues in Hongdae

ten bands worth seeing

Billy Carter psychedelic blues trio with dual female vocals and deranged stage presence

Skasucks Hongdae’s hardest working band, with a mission to create a sustainable ska scene

Dead Buttons intense rock duo with the energy of 20 tweaking junkies

Yamagata Tweakster one-man dance-pop dynamo forged in the fires of disinterest

Green Flame Boys “youth punk” band that is the aural equivalent of going through puberty

Crying Nut one of Korea’s first underground bands, looked up to by all

…Whatever That Means husband-wife interracial melodic punk band

Galaxy Express psychedelic rock trio rebounding from earlier drug charges

Huqueymsaw black metal nightmare, you never know what’s going to happen

Nice Legs foreign dream-pop trio making sublime sounds

Written by Jon Dunbar

Photographed by Ken Robinson